In a new, globalised economy, the need to be concerned about the impact of globalisation on women is increasingly significant. This is a need that is felt across the board - rural-urban, agriculture-industry-services, educated-skilled-unskilled and so on. A number of questions have arisen in recent times. How have self help groups (SHGs) empowered Indian women? How has development-induced displacement influenced the lives of women and children who have been thus displaced? What does the Global Gender-Gap Report 2006 say about Indian women? Is the bifurcation of women's lives into realms of the social and the economic a forced one? Has this been determined not by the women themselves, but by those who simplify the problem and deal with its parts rather than understand the whole and its interlinking complexities?

![]()

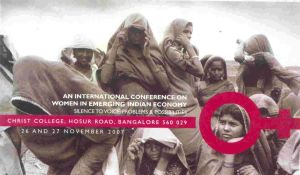

To address these questions and many more, and to explore the possibilities of alternative solutions, Christ College and Centre for Social Action, Bangalore and Drik India, a photographic initiative in Kolkata, jointly hosted an international conference on 26 and 27 November, 2007. The conference, titled 'Women in Emerging Indian Economy - Silence to Voice - Problems and Possibilities', was supported by Fredskorpset (FK), a government body under the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA). Case studies, empirical research and successful initiatives from the state, market and civil society were the key tools in the conference deliberations.

Researchers, academicians, policy makers, gender experts, NGOs, voluntary organisations, media organisations were invited from across the country to participate and share their experiences in different fields. There were also inputs from international areas too, such as Sri Lanka Tanzania and The Philippines. The conference was segmented into different areas:

(b) Mainstream development paradigm - a critical appraisal from a gender perspective

(c) Changing nature of work

(d) Changing agricultural sector

(e) Health of rural and urban women

(f) Women bringing changes in rural economy - national/international perspective

(g) Micro-credit - merits and demerits of promoting women entrepreneurship at the grassroots level

(h) Women in emerging economic sector

(i) Changing gender role in media - from silence to voice

(j) Development and displacement

In her keynote address, activist and journalist Padmashree Patricia Mary Mukhim of Meghalaya presented a paper on the Global Gender Gap Report 2006, which surveyed 115 world economies. She pointed out that while the World Economic Fourm placed India way ahead of some advanced nations like USA, France and Japan so far as political empowerment is concerned, the participation of women in the economy, their educational attainments and access to health is way below these advanced countries. India ranks 20th in political empowerment and 110th in economic empowerment. Indian women constitute a meagre eight per cent in the Lok Sabha and three per cent hold ministerial posts. In India, work-force participation of women is 34 per cent in the labour force and 21 per cent in technical and professional workforce. Comparative figures of women-participation in the work force in the US show a percentage of 60 and 55 respectively.

The Global Gender Gap Index measures the difference between the sexes in matters of economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health, survival and political empowerment. Interestingly, the Gender Gap Report throws light on the lesser-known facts about women's economic empowerment such as the duration of paid maternity leave, maternal mortality rates, and access to skilled health staff for childbirth.

Mukhim's paper also discussed a study in which the Institute of Social and Economic Change (ISEC), Bangalore, working with NFHS, drew samples from 100,000 women in the age-group of 15-50 years across 26 states. The percentage of menopausal women was highest (31.4) in Andhra Pradesh. The study added that the percentage of menopausal women was higher in rural than in the urban sector and that the highest incidence was among women aged between 29 and 34 years as against the natural menopausal age falling anywhere between 45 and 55 years with an average of 51 years. Medical findings, according to Mukhim's paper, show that early marriage among girls, the trend of malnutrition among girls and women, lack of family support and the tension of having to eke out a living to supplement the family income lead to early menopause.

Smita Premchander, Secretary, SAMPARK, a Bangalore-based NGO, said that according to figures arrived at by the banking sector, India has around 3 million SHGs (Self-Help Groups) which give loans to around 40 lakh households through extended credit. According to NABARD, the record for repayment of loans from SHGs to banks is more than 95 per cent. She added however, that the default rate is very high in case of subsidised loans that mainly cover BPL (Below Poverty Line) groups but the record for repayment of unsubsidised loans is almost 99 per cent and women do not default in repaying loans because they immediately apply for the next loan.

![]() From a conference exhibition by Drik-India, a photographer's collective: Women in the Cosmopolitans is a series of photographs

taken by Swapan Nayak, showing women belonging to a completely different liberalised and cosmopolitan niche, who

have shed all inhibitions in a spirt of partying and nightclubbing day in and day out.

From a conference exhibition by Drik-India, a photographer's collective: Women in the Cosmopolitans is a series of photographs

taken by Swapan Nayak, showing women belonging to a completely different liberalised and cosmopolitan niche, who

have shed all inhibitions in a spirt of partying and nightclubbing day in and day out.

Of the total SHGs, 90 per cent are women-only groups according to NABARD's figures. Why are there more women than men in SHGs? On the basis of her experience with SAMPARK, Premchander pointed out the reasons. Women are (a) easy to discipline, (b) wait patiently, (c) take small amounts between Rs.10,000 and Rs.20,000, (d) repay soon and easily, (e) permit external leadership and control, (f) easy to train as they are flexible, (g) expectations are low. However, inviting the active participation of women in SHGs ultimately comes down to using women rather than empowering them.

Rangan Chakravarty, media producer and editorial consultant of Ananda Bazar Patrika, Kolkata, made his presentation on 'Women and the Media through Television'. He pointed out that violence is very much a part of the entire process of communication in television. The systemic violence by television is characterised by the marginalisation of the majority. By banishing the poor from the realm of images the media renders them invisible because the have-nots, which includes a large percentage of women, are considered a nuisance, a burden that disrupts the smooth passage to a global, consumerist world. Invisibility, he underscored, is a major and strong weapon - 'out of sight, out of mind'.

Chakravarty insisted on television's need to: (i) raise a voice against the woman's body being made a site for the nation's morality; (ii) question and debate on how and why women are increasingly made targets of political violence and (iii) recognise that women are the worst sufferers of economic violence. Representation, according to him, need not necessarily mean empowerment because representation also depends on which women get represented in the media, how and in what context.

Dr Walter Fernandes, Director, North Eastern Social Research Centre, Guwahati, pointed out how globalisation will add to the woes of women who have already been displaced in the past due to political reasons and ethnic conflict because globalisation has led to large-scale acquisition of land by the corporate sector in general and the private sector in particular. He added that large-scale land acquisition for profit-oriented industrialisation also led to large-scale mechanisation raising unemployment levels persistently. Forced displacement makes women internalise the dominant ideology as a coping mechanism.

For example, when outsiders enter a township, they bring along with them the ideology of consumerism and material affluence. This influences the male residents of the township who begin to spend a large part of their income on clothes and entertainment, leaving women with little share to run the family even when the men's incomes rise. Forced to seek economic alternatives to feed the family, many women often get into prostitution. In most mining towns in Jharkhand for instance, a specific area called Azad Basti has evolved over time where men who leave their families behind to work in the mines, visit this place to buy sex. Development-induced displacement triggered by globalisation, would deprive women of whatever little autonomy they had.

![]() From the conference exhibition by Drik-India: Dalit Women in Rural India, a photographic oddyssey by Sudharak Olwe into the living hell that is the life of the Dalit woman in India who remain excluded from all women-centric bills and laws discussed in and passed by the Indian parliament.

From the conference exhibition by Drik-India: Dalit Women in Rural India, a photographic oddyssey by Sudharak Olwe into the living hell that is the life of the Dalit woman in India who remain excluded from all women-centric bills and laws discussed in and passed by the Indian parliament.

Gloria Ramaine de Silva of the Center for Family Services (CFS) Sri Lanka, in her presentation on 'The Changing Agricultural Sector - A Gendered Approach', explained that the participation of women in the agricultural sector in Sri Lanka has diminished over the past two decades. She added that in spite of upward social mobility brought about by free education and health care, the overall status of Sri Lankan women has come down. Gendered social norms, armed conflict, slow economic growth, accelerated development programmes, combined with the chronic apathy and lack of political will among legislators have resulted in blocking the attainment of gender equality and equity in keeping with international norms.

Ichikaeli Maro, Chairperson, Tanzania Media Women's Association (TAMWA) in her paper on 'Women in the Emerging Economic Sector' pointed out that in most societies in Tanzania, the woman who could not produce a male offspring ran the risk of being divorced and the man would marry another woman to keep the family line going. This led to large-sized families because wives would wait till a son was born and large families led to greater poverty. She underscored that proponents of gender equality picked four priority areas to better the condition of women. These are (a) education, (b) legal literacy, (c) economic empowerment and (d) political participation, which were adopted immediately after the Beijing Conference in 1995.

The conference explored and assessed the role of women in the changing economy and the role of the state, market and civil society initiatives under the present globalised economic environment. It identified some of these challenges in terms of possible creation of pockets of resistance, unequal growth, polarisation, coping with new reforms in the constitution and last but not the least, a critical understanding of who would be the ultimate beneficiaries of these changes. It went on to study how alternative institutional mechanisms and innovative practices could strengthen gender relations in developing nations.

The Indian woman keeps fighting many wars on different fronts. The battle is the battle of life where she also must encounter her share of oppression and humiliation. While new schemes are devised and new methods are invented to make life easier for less privileged women, their degree of empowerment remains a matter of grave concern. This conference drew attention to this issue with feeling, objectivity and diversity.