Four years ago when the farmers of Vengaivasal village (around 20 km South of Chennai) banded together to revive their lake, they were feted for their foresight. Farmers there say after the lake was rejuvenated their wells have not been going dry, even in peak summer. They moved to a round-the-year crop cycle from rain-fed agriculture.

![]() A drying Vengaivasal lake after two poor monsoons. Unbridled extraction of groundwater continues in neighbouring irrigation wells. Pic: Krithika Ramalingam.

A drying Vengaivasal lake after two poor monsoons. Unbridled extraction of groundwater continues in neighbouring irrigation wells. Pic: Krithika Ramalingam.

But ironically, for the last two years, the rejuvenated water body and (recharged) groundwater wells slake more the thirst of Chennai and its suburb than those of the fields.

Since the mid 1960s the Chennai's water managers have looked elsewhere to meet the needs of urban agglomeration (city plus its neighbouring 302 municipalities and panchayats): from the well-fields of Arani-Kortrailaiyar River (A-K) basin to the non-flowing Palar basin. Over the last five years the farmers of the two districts have started selling water from their irrigation wells to the detriment of cultivation in their own land and those of their neighbours.

Vengaivasal's 104-acre lake was deepened and encroachments removed only in 2001 under the NABARD-funded Water Resource Conservation Project-II. A Water Users Association (WUA) was formed and the villagers given the responsibility of maintaining the irrigation lake and channels. Efforts were taken by the Kancheepuram Collectorate to recharge the ground water.

But it is a divided panchayat, presently. The farmers trained to preserve their water resources find themselves fighting a losing battle with those among them selling water from their irrigation wells and with the water mafia. Most of the selling is being done illegally. Farmers have obtained permission to sink wells for irrigation purposes, but separate permits are needed for using irrigation wells to sell and transport water under the Chennai Metropolitan Area Groundwater (Regulation) Act, 1987.

Vengaivasal is centrally located to serve most of the southern suburbs of Chennai, along the Velachery-Tambaram High Road and other burgeoning predominantly middle-class suburbs further south. M Venkatesan of Pudhu Vellam, a network of WUAs, says: "the farmers of neighbouring Medavakkam village have started selling water meant for irrigation. Initially, it is from the wells abutting the road. But as the summer progresses, more fields become fallow and lorries gain access to interior wells too. When we protest the authorities ask us to give up rights to solve the permanent thirst in Chennai."

The average ground water has dropped 15 feet over the last summer to around 50 ft now. And the lake that had brimmed over with monsoons in 2001 and 2002, recorded only half its capacity in the two subsequent years. "If the water spills over into kalangal (where the surplus is stored), the farmers know they can go ahead and cultivate rice. For the last two years, it has been a guessing game," says Venkatesan. More south, into the Palar basin, the village of Pazhayaseevaram has become a case in point for the devastation that over-exploitation can wreak. A project by the Department for International Development UK through the Infrastructure and Development Divisions Knowledge and Research programme (published September 2004), has established that drinking water supply for drinking purpose for the local communities has come down steadily and the area under cultivation has gone down.

• Researching turbulent waters

• Water canals or treasury drains?

Also, wells have either been deepened or abandoned due to steady fall in the water table. (The average depth of the present wells in the Palar basin is 69 feet, according to a study by Madras Institute of Development Studies.) Farmers have taken recourse to rain-fed agriculture as their wells have failed and the irrigation lake is no more able to meet their needs. Paddy cultivation has come down from 159 acres annually to 10 acres, leading to loss of livelihood among landless agricultural labourers. The study notes: " since the loss in agricultural work is so high, despite the non-agricultural work (from a sugar mill), their workdays have decreased from 250 to 190 (24% decrease). For women the reduction is from 190 to 150 (21%)."

The socio-economic cost of such unbridled exploitation of water, though not well documented, has already been observed in the neighbouring district of Thiruvallur (where the Arani-Kortrailaiyar basin and the three reservoirs feeding Chennai are). S Annamalai of Centre for Rural Women Education for Liberation says with the drop in employment opportunities there has been a definite increase in lumpen elements and urban migration. Anti-social activities such as brewing of illicit liquor have been on the rise in the last decade.

Not surprisingly, the farmers of Thiruvallur and Kancheepuram districts are up in arms against selling of groundwater. "Underground water exploitation has been happening for 40 years now and its impact is for all to sea. In Minjur and neighbouring areas, there is seawater intrusion into the sub-stratal water table up to a distance of 5 km in-land. Agriculture in Minjur is now impossible. This phenomenon would continue along the Arani-Kortrailaiyar basin if groundwater exploitation is not stopped forthwith," says Annamalai.

In villages like Velliyur, Vishnuwakkam, Magaral, Selai, and Kaivandur, Chennai Metrowater extracts ground water 24 x 7 with as many as 30 ten-horsepower pumps. With dwindling groundwater, the decline in agriculture is already apparent in the last two years that water utility has started pumping from private irrigation wells.

"When the water utility realised its investments in well fields were not cost effective, they started leasing water from private wells. But the farmers were not given complete information including what could happen to their water table, nor were the contract made transparent," avers Annamalai.

And his charge is substantiated by an Indo-French study on the "Tripartite agreement in peri-urban Chennai: Rural impact of farmers selling water to Chennai Metropolitan Water Board". Authors Marie Gambiez and Emelie Lacour note that while the number of farmers selling water has increased from 12 in 1993 to 22 in March 2001 in the village of Magaral, the duration also increased from 12-hours a day for four months in 1993 to round-the-clock, round-the-year in 2001. Though the agreement said farmers must give 18 hours water per day "in reality we saw that the number of hours per day was never regular. In fact, the CMWSSB sometimes asks farmers to give water for 24 hours and other times for 12 hours, depending on what it needs."

And as is the case everywhere, the local body had no role to play in the negotiations or in regulating the amount of water extracted. Says, M G Devasahayam, managing trustee of the Chennai based Citizens Alliance for Sustainable Living (SUSTAIN): "And this is leading to the conflict, be it in the Telugu-Ganga project, New Veeranam augmentation project or the farmers around the city. When the Telugu Ganga Project was envisaged to bring 15 TMC of water from Krishna through the drought-hit Rayalseema, the farmers were left out of the talks."

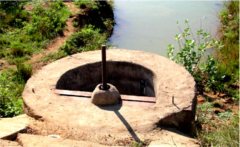

![]() A shut sluice gate at the Vengaivasal lake, with irrigation water being rationed following falling levels. Pic: Krithika Ramalingam.

A shut sluice gate at the Vengaivasal lake, with irrigation water being rationed following falling levels. Pic: Krithika Ramalingam.

The contract between Andhra Pradesh and Tamilnadu was to bring Krishna water exclusively for Chennai though canals. Had the farmers of Rayalseema been consulted (not necessarily through their gram sabha but even as stakeholders) they would have pointed out how unfeasible it is to export water through the drought-hit region to another state without meeting their needs. "Today, the pilferage is a leading cause for Chennai not getting the allotted quantity", says Devasahayam.

Likewise with the New Veeranam (an irrigation lake that is a reservoir for the surplus from the Cauvery River) Project. "While the quantum promised was 180 tmc after the irrigation needs are taken care of, if the water managers had held grassroots consultation, they would have realised it would be impossible to conjure it up. Now well fields like those in Arani-Kortrailaiyar basin are being dug and the farmers are apprehensive of loss of irrigation water," says Devasahayam.

(An April 2, 2005 Madras High Court decision endorsed the Tamilnadu Government's action of drawing sub-surface water from riverbed of Kollidam, that drains from Veeranam lake. Farmers of Cuddalore and Perambalur are now considering appealing the verdict in the Supreme Court.)

But Chennai continues to be as parched as before the schemes. Chennai Metro Water Supply and Sewerage Board in its master plan has estimated a water requirement of 1,504 million litres per day at 150 litres per capita daily for the Chennai city and 100 litres per capita daily for the rest of the urban agglomeration, by 2011. Domestic per capita supply, however, is projected at 1409 mld. This projection depletes with poor monsoon, dwindling resources in Palar and Arani-Kortrailaiyar basin and is hinging on the arrival of 930 mld from Krishna River (according to Metrowater's Master Plan). The water managers are left with little choice but to buy farmer's rights to pump water from the A-K basin and are in the process of setting up an authority to monitor its functions.

But with lax implementation of regulations, the rapid environmental degradation is soon becoming a reality in the A-K Basin. G Dattatri of SUSTAIN says two sets of regulations to monitor the use of groundwater are in place, "but it is the case of the lawbreaker and the implementer being the same person. Chennai Metropolitan Area Groundwater Regulation Act, 1987 vests powers with para-statal bodies such as Metrowater to issue licences for boring wells." The Act does make the sinking of wells contingent on availability of groundwater. But Metrowater is itself proceeding to extract water over and above the contracted amount with no responsibility for the dwindling supply.

Another water law meant for the rest of the state (excluding Chennai Urban Agglomeration) the Tamil Nadu Groundwater Act, 2003 - is not yet in force as the rules are to be framed. As long as water is going to be linked with property rights - that is the person who owns the land can choose the use of sub-stratal water - and not considered common resource, such blatant exploitation will continue, Dattatri says.

In the meanwhile, the farmers of Thiruvallur and Kancheepuram are doing just that. With a profit margin three times that of cultivating rice, the farmers are sorely tempted to make water their commodity while others in the neighbourhood suffer, say activists Venkatesan and Annamalai.

As a means to overcome this rural resentment, development sociologist with International Food Policy Research Institute Ruth Meinzen-Dick says all stakeholders such as farmers without agricultural wells, in-land fisherman and women should be involved in dialogues for contracting water transfer to urban areas. Negotiated approaches that allow farmers to voluntarily reduce water use and profit from transfer to cities are likely to cause less resistance and less loss of livelihoods in rural areas, she says.

In Chennai recently to speak on "Rural-Urban Water Transfers" at M S Swaminathan Research Foundation, Meinzen-Dick says farmers are willing to share their water if they are well compensated and provided they know it is for drinking water. "In myriad of casesespecially in the western United States, Chile, and Mexicoindicate considerable scope for negotiated transfers with mutual gain. Under some of these arrangements, cities can pay for investments in rural irrigation water conservation and then use the 'saved' water. They can also pay farmers to not irrigate some of their land or buy outright rural water rights." But in India, most of the steps taken have been outright expropriation.

However, she is quick to add that villagers resent water usage by industry and wasteful usage by the urbanites. Faulty rainwater harvesting techniques that do not take into account local hydro-geological features have done precious little to the water table. Becoming more aware about their customary rights, farmers want the city dwellers to take more active participation in protecting their own water sources before looking villageward.