Imagine you tweet a photograph of a well-packaged, expensive milk carton. And you immediately receive a reply to that tweet from a man asking you if that milk is from your breasts. Shocking, isn’t it? But it is just an example of the kind of abuse women face with shocking frequency on the big bad World Wide Web today.

If you thought being whistled or ogled at on the street was bad enough, and that networking online from the safety of your room was a safer bet, think again. Women aren’t spared even on the Internet and increasingly find themselves at the receiving end of abuse and harassment, often even sexual in nature, in the virtual world.

Delhi-based television journalist Sagarika Ghose says there is a massive amount of hostility, especially towards high-profile women, “women who are seen to have opinions and women who are seen as ‘liberal’ or ‘secular’.” She herself has been threatened with gangrape, public stripping, threats to kidnap her daughter and even death threats.

Chennai-based journalist Kavin Malar has been at the receiving end of abusive messages on a social networking site from a self-proclaimed AIADMK supporter.

Secretary of the All India Progressive Women’s Association, Kavita Krishnan, has been threatened with rape during an online public chat about the rising cases of rape and violence against women in India on one of India’s most well-known news portals. “Kavita tell me where I should come and rape you using condom,” she was asked.

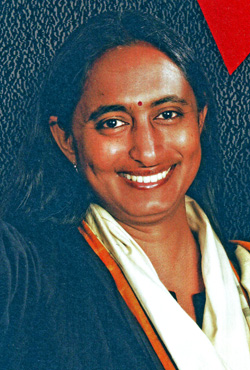

Playback singer Chinmayi Sripada, who has also been abused on social networking sites like Twitter, says, “An extremely average man is having trouble coming to terms with the financial security and the education that a woman has today.”

Playback singer Chinmayi Sripada. Pic: Shradha Borawake

Women as the target

In an exploratory study of women and online verbal abuse in India by the Internet Democracy Project (IDP), titled ‘Don’t let it Stand!’, it was found that very often threats were simply because the person was a woman. The study systematically considers in-depth, the ways in which women face and counter gender-based abuse in online spaces. It is this study that highlighted instances such as the tweet about a milk carton referred to earlier.

The IDP study cites the example of Sagarika noting that while her husband, Rajdeep Sardesai, also a well-known journalist, gets viciously attacked on Twitter for his views, the vitriol that he has to face is not of a sexually violent nature.

Another person quoted in the IDP study says the real problem is when “they do not talk about my thought process, but about my appearance”.

Advocate and founder-member of Mumbai-based Technology Law Forum, N S Nappinai says it’s almost as if the easiest way to threaten a woman is to tell her she will be stripped or raped. “And it spreads easily on the Internet.”

Chinmayi identifies this as “playing on the collective, regressive belief system that has been established in India that a woman who is sexually assaulted in any degree will be the one facing shame and not the aggressor.”

And all this is done knowing that unlike on the streets, where there is a face to the abuser, in the online space, one can get away without revealing one’s identity. Sagarika says, “It’s easy to attack women on social media as you can hide under the cover of anonymity.”

While it may not be common or easy to call someone a ‘slut’ or threaten to gang rape her in the real world, there is the feeling of being able to express these sentiments freely, without fear, on the Internet.

In IDP’s study, Mumbai-based blogger Trishna is quoted saying, “There’s a mob mentality which is as real as on the street. Gentle people who on a road would not get down and hammer people, given the chance to do it virtually, they [won’t think twice]”. She adds, “...This virtual interaction...I think a lot of people misuse the Internet because anonymity gives you so much freedom.”

The power of anonymity

So what does one do when faced with such threats and abuse online? Those like Sagarika, Chinmayi and Kavita have gone to the police and lodged a complaint.

In Chinmayi’s case, at least one person was arrested for harassing her online. However, Sagarika says that since a number of these Twitter handles are anonymous, the police do not seem to be able to track them down, which was the case with her. A similar problem in Kavita’s case because of which the police are closing her complaint, she says.

This is a common problem faced by many when reporting such cases.

Says D Roopa, Superintendent of Police, CID-Cyber Crime, Karnataka, “Very often it is difficult because even IP addresses are masked. The challenge with cyber-crime is that it is transnational. There are so many tools available to remain anonymous.”

She gives the example of a Bangalore woman who filed a complaint in 2010 after she found morphed photographs of herself doing the rounds on more than 3000 websites. Despite a court order to get these sites blocked, CERT-In or Computer Emergency Response Team-India, the national nodal agency for responding to computer security incidents as and when they occur, has not done so. The only positive in this case is that the accused, found to be her ex-boyfriend, has been charge-sheeted. However, the victim continues to live with the fact that the obscene photos are still in the public domain.

Roopa explains that since companies like Facebook and Twitter are headquartered abroad, “they take about three months to reply about the identity of a person. When it comes to deleting content, that gets done quickly. But they take time to give information about who posted a photo or comment.”

Take the case of Mumbai-based finance professional, Nidhi (name changed to protect identity) who has been battling a cyber crime case for more than six years now. In 2007, Nidhi filed a sexual harassment case against the partner in the organization she worked in. When the accused was arrested, a popular tabloid in the city reported the case, revealing details about her identity. The online version of this particular article received several slanderous and vulgar comments about her which failed the moderation, because of which she filed a complaint with the cyber crime cell of the Mumbai police. Subsequently, several other websites were found to be carrying slanderous comments about her, many even referring to her as a ‘dance bar girl’, ‘legal terrorist’ and a ‘prostitute’. She has since written to Google requesting them to remove the links to some of these websites. “Google advises action against the hosting sites to curb this cyber slander,” she says.

In June 2012, Nidhi filed an RTI application requesting information from the police about what action has been taken on her complaint against the websites. “I have to use an RTI to find out about the status of my own complaint”. A month later, the police responded to her RTI application saying that letters had been sent to Google, Nabble, 498A[dot]org but no response had been received. It also stated that a NC (non-cognizable) was filed in September 2010 and was closed as a civil case. “They never even informed me when they closed the complaint and the signature on the NC is not mine,” she says.

On 3 November 2012, the Chief Metropolitan Court passed an order directing CERT-In and Google to delete a set of defamatory blogs against her. The Police is empowered to obtain such an order from the Court as per section 69A of the IT Act, she says. This section refers to the power to issue directions for blocking public access of any information through any computer resource. Even a month from that date, Nidhi says some of the defamatory comments remained online. She again filed RTI applications, one seeking a copy of the court order from the Police, and another seeking the status of implementation of the said order by CERT-In. It was only on 28 December 2012 that the court order was implemented by the Department of Electronics and IT, she discovered.

Is the law equipped to deal with the culprits?

•

Speak-out sisters on the Net

•

Tribunal verdict raises hope

The inordinate delays, inaction, abrupt closure of complaint without informing her - Nidhi continues her battle with the enforcement and prosecution authorities to this day. She says many obscene comments continue to remain online. “I don’t think the police are adequately trained in the relevant laws,” she says.

Her doubts are partly confirmed by the IDP study where it mentions an official of the Mumbai Cyber Crime Police Cell admitting in an interview that the law is particularly handicapped in cases where the person is based abroad, and not within Indian jurisdiction. “Apparently Facebook shares details of its users only in issues of national interest, like terrorism,” the study quotes one journalist Fathima as saying.

When companies like Facebook and Twitter or any other foreign-headquartered organization do not respond to removal of objectionable content or give details about the person who has posted such content, the police can actually use what is referred to as the Letter Rogatory. This is where the Indian courts can use the assistance of foreign courts for judicial assistance, and is usually done through the Central Home department. But expectedly, these take time.

Nappinai says there is a lack of awareness among enforcement authorities. “They’ll say the server isn’t in India. That’s not something you want to hear. The problem is, and I’m speculating here, police has a reluctance in registering a case because of statistics,” she explains.

Cyber crime cases are fairly new. Police stations in India have got computers only in the last few years and they are mostly used for typing purposes. “More awareness is required. And technology is something you need to keep yourself updated with,” says Roopa of Karnataka’s CID.

Nappinai also refers to instances of police opposing the filing of cyber crime complaints. “They say they won’t be able to find out. The cyber crime cell sends you to law and order, law and order says they have forwarded it to cyber crime. They ask you why you got the content removed before the investigation.”

Advocate Dr Debarati Haldar says she had a close friend who was abused online through morphed photos that were circulated. “She felt humiliated and saw no reason to go to the police”. This prompted Haldar to set up the Centre for Cyber Victim Counselling in Tamil Nadu’s Thirunelveli district in 2009. She gets about 30 to 40 cases every month. She says, “Victims need to be stubborn. Because otherwise it affects the police also.”

She says she has heard of a police inspector telling a girl, “Your husband also must be calling you names at home, you don’t file a complaint for that, so take this (online abuse) also in the same way.”

Reluctance in seeking legal help

Perhaps partly due to ineffective redress under law, and partly due to social and personal inhibition, the idea of visiting a police station and following a case through to its logical conclusion seem to be significant deterrents for many who face abuse online. Haldar says, “When I ask women to report cases of trolling to the police, they say it’s ok, it’s no big deal.”

Secretary of the All India Progressive Women's Association, Kavita Krishnan was threatened with rape during an online chat on a leading portal. Pic: Kavita Krishnan

Secretary of the All India Progressive Women's Association, Kavita Krishnan was threatened with rape during an online chat on a leading portal. Pic: Kavita Krishnan

Most often, women just want the obscene content to be removed, be it textual or visual. Haldar says in her experience she has seen very few women who want to push their case through. “Victims say remove the offensive post or photo and then they ask for the case to be closed.”

Singer Chinmayi attributes this to the fact that a lot of people do not have the time or energy to spend on such cases. “They want the content removed and have a peaceful life. No one wants to visit a police station unless really necessary. And lawyers also advise it is best to resolve cases out of court if the matter isn’t too serious,” she says.

“Maybe women feel that there will be a stigma attached if the case drags on. People even want to settle amicably,” says Roopa.

Th reluctance in using law to combat online harassment is a trend that even IDP saw among those they spoke to. Many women felt it was better to ignore and allow the incident to die a natural death. In some cases, even family members object to going to the police.

Many others use the option of blocking people on sites like Twitter. Bangalore-based journalist Dhanya Rajendran did this when a man repeatedly sent her abusive messages on Twitter. “He was going on abusing. I first was polite. Then after he ranted a lot, I said get lost! So the guy threatened he would commit suicide! Simply to unnerve me, I guess.” Dhanya reported the account to Twitter and the account was eventually blocked.

However, even though Twitter suspends an account if the user is found guilty, they cannot stop the same user from accessing the site using another email address. It’s because of this that Dhanya says it may be really better to ignore because “Twitter has become a platform for many anonymous people to unleash their aggression without attracting punitive action.”

Nappinai however recommends that one should take a print-out of the defamatory/offensive content, if possible in the presence of a public notary, and then file a police complaint.

‘Put norms in place’

Even as online abuse is on the rise, more often said to be anger-driven rather than motivated, the fact is that there is very little to actually stop the abusers. The IDP study notes that uncertainty about who the attackers ‘really’ are in a world of fluid identities, fears about heightened attacks, a lack of awareness, and a mistrust of legal systems all combine to serve as potential barriers to addressing what is a growing problem for women across the world.

Some feel that it is not right to attack anonymity in an attempt to tackle incidences of trolling. Anonymous speech is necessary to protect an individual’s privacy and right to freedom of speech. As Snehashish Ghosh, Policy Associate, Center for Internet and Society says, “...anonymity can be abused but we cannot have policy and regulations based on fringe cases in the same way that we cannot ban knives because it can be used to stab people as well as cut vegetables.”

This is also a reason why there are objections to Section 66A of the IT Act. “Section 66A was intended to be anti-stalking, anti-phishing and anti-spamming provision. But in its current form it is vague and ambiguous and can be easily abused. It uses terms such as annoyance and inconvenience which does not have a clear meaning in criminal law,” Ghosh explains. Section 66A of the Information Technology Act pertains to punishment for sending offensive messages through communication services.

Kavita Krishnan says that instead of trying to bring about change in the nature of the Internet, the community needs to put in place a set of norms. For example in her case, the company that hosted the chat should have moderated the session.

The fact of the matter is that law is just one aspect of this growing menace. This unrest against opinionated women, expressing threats and hatred, seem to be a reflection of a deeply patriarchal society fighting against the progress women have made. Overall, Internet penetration in India is about 12 per cent of the population. And it would be fair to conclude that those who use it are educated. So the abusers are also educated. How many men are threatened of being stripped and raped? Why is there this perverse desire to attack women?

The IDP study quotes British journalist Laurie Penny explaining this: “An opinion, it seems, is the short skirt of the Internet. Having one and flaunting it is somehow asking an amorphous mass of almost-entirely male keyboard-bashers to tell you how they’d like to rape, kill and urinate on you.”