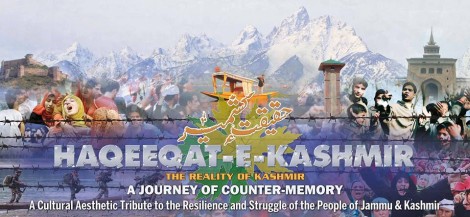

Ironically, it was Zubin Mehta's concert organised by the German Embassy and the state to score political brownie points that helped orchestrate and showcase Kashmir's rich legacy of creative resistance. Stung by the move to prove that normalcy had returned to Kashmir, a parallel concert was organised in a municipal park. Termed Haqeeqat-e-Kashmir, the concert displayed the varied ways in which Kashmiris continue to express their dissent - through plays, poems, skits, music performances, mime and so on.

Zareef Ahmad Zareef, Kashmir's acclaimed poet, satirist and social activist, helped stage the event with his literally hands-on approach, personally ferrying sticks and planks needed for assembling a platform. Best known for his Taaran Garee (meaning trickery or skullduggery) - a set of verses that lampoons the duplicity of political leadership and some aspects of Kashmiri society - Zareef's participation set the tone for the show.

The links in the chain of resistance and necessity for historic continuity was underscored by playwright Arshad Mushtaq's 14-minute play Be Chus Shahid (I am the witness) which talks about the generational transition of responsibility that all people resisting against oppression have to shoulder. Featuring students and not professional actors, Mushtaq's play was a literal rendition of letters that hinted at the sufferings and pain of what the Kashmiri people have been subjected to. Leaving many people in the audience in tears, it emphasised the central role that memory plays in resistance - reserving it not just as remembrance, but one endowed with responsibility.

Indigenous art forms

Mushtaq chose to draw on Kashmir's indigenous form of theatre - Bandh Pathray - for inspiration. He explains how this form of folk theatre has traditionally been used to express dissent and that its strength lies in its ability to use burlesque and satire to analyse current events. "You had Darz-e Pathray that ridiculed kings, Pogol Pathray that mocked the Moghuls and Bugar-e-Pathray that ridiculed landlords. It is an ideal form for an absurdist play like Waiting for Godot."

One of the features of Bandh Pathray is the way performers mingle with the audiences so that there are no dividing spaces. The Haqeeqat-e-Ehsan concert also saw this free intermingling of spaces with even Zareer Ahmad Zareer choosing to sit on the grass and not on one of the chairs. Majid Maqbool, writer and Features Editor of Greater Kashmir, who attended the concert believes that this element of interaction among participants and the audience was particularly pleasing.

Another journalist Shahnaz Bashir noted in his report how even the police turned into interested spectators.

Resistance through rap

Kashmiri youth have also shown a remarkable ability in recent times to synergise regional concerns with new forms in music and global trends. The ability to fashion music of real time protest that not only rings true on the streets of Kashmir but also informs the world outside, is exemplified by the emergence of rap and hip hop artists, such as M C Kash who burst upon the scene in 2010 with his "I Protest."

One such rapper, scheduled to perform at the Haqeeqat-e-Kashmir concert, but unable to do so because the organisers ran out of time, is 23-year-old Shayan Nabi, aka Shyn 9. He explains that the coming of the Internet to the Valley in 2009 brought with it an introduction to hip hop as a way of "saying what you really feel."

"In 2009-2010 I, like others, discovered how we could use music to protest. Hip hop had evolved as a way to resist slavery. As a Kashmiri I can understand that. I felt this is my thing. I couldn't go out on the streets to throw stones, but I could hurl words and I chose the English language so that the world would get to know."

"Before I could do my own stuff, I needed to learn and spent two-three years doing that. I started giving my music for free to other rappers. Since last year I have begun doing it entirely on my own and soon I hope to present an album Shaheed-e-Kashmir, as a tribute to the martyrs," says Nabi.

The eight or nine-track album will look at the 1800s and then at the first sacrificial deaths of 1931. It was on 19 July, 1931 that Kashmiris openly challenged the legitimacy of rule under the Dogra king. Other tracks look at the nineties, 2008 and 2010 - momentous years in Kashmir's resistance movement. There is also a track on the hanging of Afzal Guru and on the mass rape by security forces of women at Kunan-Poshpora.

Nabi researched archives and the net to get his understanding of events and memorialising. The social medium also opened up an exciting collaboration with Mumbai-based rapper Ashwini Mishra. "Here was a guy who was in Mumbai but talked of Kashmir. I used to follow his tweets and knew he talks the real stuff. We wanted to do a joint thing on the hanging of Afzal Guru but there was curfew in Srinagar then, so I told him to go ahead and said I would set it to music."

That is how Mishra, who does a lot of rap as a means of protest, did a track on Afzal Guru ("We hung a man on circumstantial evidence and to me what is tragically worrying is we didn't even let his family bury him.") Afzal Guru's sudden execution and the fact that sections of people were celebrating it led him to the conviction that he needed to put out a song that brings in a different point of view. "It was very popular with Kashmiris but I also got a lot of threatening emails from others." This has not perturbed Mishra who believes that if the mainstream applauds his work then he is doing something wrong!

Mishra, who was for a brief while into Indipop, has been writing songs as part of his activism for five years. "I've written on movements in Koodankulam, on the arrest and brutal treatment of adivasi teacher Soni Sori and on Binayak Sen. I started rapping to try and bring in perspectives that are not in the mainstream. As I met many Kashmiris and listened to their perspectives, I realised how people have so many warped ideas about Kashmir. They don't know that it existed historically as a separate entity even before Pakistan and India were created."

The different ways in which Kashmiris are exploring creative forms to counter the mainstream and official narrative through the arts and culture is encouraging.

Says Mushtaq, "Haqeeqat-e-Kashmir came as a stone of resistance to the state's bid to dilute the voices of the people. Another significant feat it achieved was

that political players across the board realised the importance of arts and culture in the Kashmir scenario, I see it as a beginning of a much more creative means

of protest that will dent the dominant discourse of the anti-people state".