After 15 years of continuous rule by Sheila Dikshit of the Congress party, the political future of the national capital is now in flux with the Assembly election resulting in a hung assembly. The capital began its journey to this point about three years back when the rumblings of political change began.

It started with the Commonwealth Games scam in 2010, where money was diverted towards personal gains, illegal contracts were drawn up and politicians found complicit. It heaved with Anna Hazare's anti-corruption movement in 2011, where the man went on a fast for days demanding the government enact an anti-corruption law, which brought the country into solidarity with his cause.

While in the throes of it, it seemed like these two events were the peak of things to come in Delhi, but they were in fact the waves that were pushing the national capital on to a day of tangible difference. Now, with the results of the recent Vidhan Sabha elections in hand - the massive defeat of the Congress here, and the small margin of difference between the current two largest parties, the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Aam Aadmi Party - it is suddenly possible to quantify the desire for change. There are, however, even larger takeaways from these elections, as we will see.

Two lessons on losing

There are two ways in which the Delhi elections have shown that the "winner-takes-all" mentality needs a rethink. This election has shown that losing can be constructive if used well, and losers can even outshine winners.

Firstly, with both parties appearing lofty and self sacrificing as they decline power, what we are seeing is a new found understanding and respect for the role of the Opposition. While Delhi has voted for a hung assembly, a coalition seems improbable this time around. Being the single largest party, the BJP has been given the first picking in government formation. But in a surprising irony, they have said, Pehle aap. Dr. Harsh Vardhan, the BJP's chief ministerial candidate, says he is happy to sit in the opposition, as his party is not willing to engage in any shady deals to reach 36 seats. The BJP has long been accused of being a weak opposition, and though they stepped up their game over this year with their participation in Parliament, perhaps this election can pave the way for further re-invigoration.

AAP, too, is reluctant to take office. Their appeal is somewhat anti-politics, and their ideology is alternative-politics. Working in tandem with India's grand old parties with their antiquated notions of how politics must work, their stand on ceremony, and their disconnect from the people, would be antithetical to AAP's promise. Arvind Kejriwal, the party's leader, said to a TV channel that an alliance was out of question, as there is no difference in-principle between the Congress and the BJP. The AAP is ready for re-elections or to sit as a "responsible opposition".

What looks increasingly likely, then, is that Delhi will go to polls again, in six months, following a period of President's Rule, which is the protocol in the event of such a situation. Delhi will most likely vote along with the General Elections in May 2014.

The BJP contends that it won because of its development agenda and track record, but the fact that AAP managed to get nearly as many seats as they did and deny them a clear victory means that the BJP is up against almost as many people who don't buy its ideology as those who do.

•

A tipping point for Indian democracy

•

When idealism isn't impractical

Democracy is run on majorities, but sizable minorities in terms of vote-banks and in terms of seat-share have immense power to affect the majority. The position of the Opposition is not one to be taken with bitterness over losing, or complacency in involvement and we are seeing an embrace of this idea in the two leading parties.

Secondly, while BJP is the single largest party and closest to the seat of power in Delhi right now, AAP is really the hero of the show. Winning and losing elections is routine. The BJP has done this for years since its formation in 1980, losing more than winning. But performing well in an election under circumstances that makes failure seem more probable than victory, is truly remarkable. A comparative analysis of the odds that the AAP and BJP were up against prior to the elections, and the differences in their seat-share post the elections, will depict this.

When losers outshine winners

Even on numbers alone, the difference in seats that the two largest parties won is slim - a mere four seats. The AAP scorched the Congress by eating up its constituencies, and in the specific case of Dikshit's constituency which Kejriwal won, he did so by a margin of over 25,000 votes.

Delhi had a record voter turnout of 67 per cent this time, beating the previous high of 62 per cent in 1993. It also registered the lowest exercise of the newly introduced 'None Of The Above' (NOTA) option with the tally at less than 1 per cent. Both these are being attributed in part to the active campaigning of the AAP who encouraged people to vote, albeit for them, and gave them that alternative option, so as to negate any of the usual excuse of people who choose to not vote, which is that there is no worthy candidate.

Analysts had predicted that AAP would only shift the balance between the obvious two powers but ultimately not be able to spring any major surprise. The possible effect of AAP on Delhi politics was being compared in some quarters to the effect that the Yeddyurappa-led Karnataka Janata Paksha had in Karnataka, where it did not win itself but it managed to weaken the BJP enough to allow a Congress win in the state. But AAP did not just shift the balance from the Congress to the BJP, it very nearly grabbed office itself.

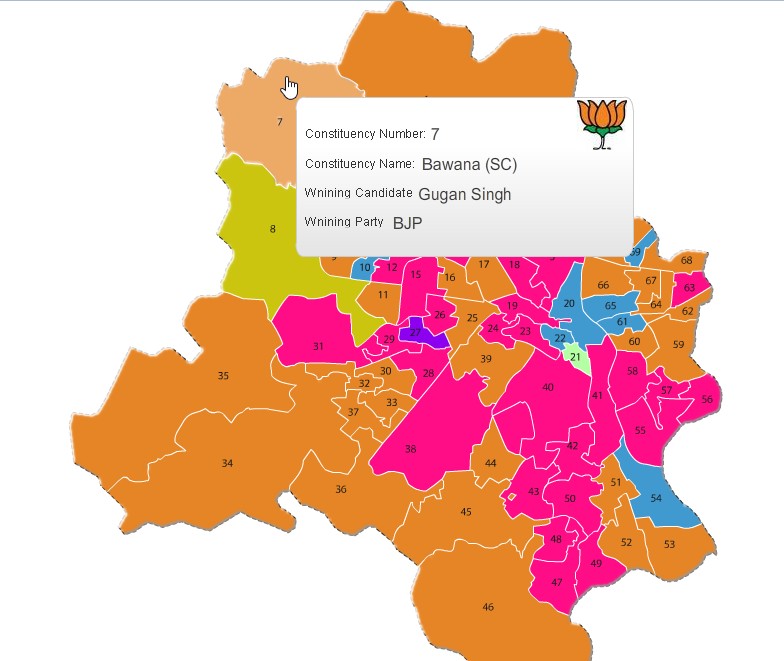

A look at the constituencies in which AAP won this year shows that they are mostly the constituencies which the Congress had won in 2008, such as central and south Delhi areas. Likewise, the BJP has garnered Congress constituencies around the borders. AAP has not eaten into much of the BJP's areas from 2008 but by chipping into the Congress' areas, it has weakened the latter. This has served as both a strength and weakness for the BJP - strength, because it diluted the Congress, and weakness because AAP made its own gains out of the dilution.

Winners by constituency: See browsable map at

http://www.mapsofindia.com/assemblypolls/delhi/election-results.html

Congress leader Digvijay Singh agreed that the AAP had hurt the Congress, not so much the BJP, in an interview to a TV channel. According to him, the party performed well because they managed to wrest away the Congress' former faithfuls, such as those in slum colonies and from economically weaker sections. This is in no small part due to its down-to-earth appeal and method. But AAP's appeal went up the class-ladder as well, with Kejriwal winning in the affluent New Delhi constituency, which is prime real estate and houses several bureaucrats. The party has also seen a large following of NRIs, young corporate professionals, and students, mainly with an urban background.

If Delhi goes to vote again in six months, it is unlikely that the Congress will regain much of its foothold, with no opportunity to be in active politics during the period under President's Rule. The BJP and AAP are the ones who stand to make gains or losses in this time. The BJP can make up for time wasted in the internal scuffle over choosing Harsh Vardhan as their chief ministerial face. They can also capitalize on the mood of the national elections, drawing upon the branding around Narendra Modi as their prime ministerial candidate, to distract voters in Delhi from state politics and push them to think nationalistically instead.

AAP on the other hand can use the time to expand on its areas of influence, and milk its near-victory as inspiration for the next round. For the first time, they now have something quantifiable to show their detractors, skeptics, and even opponents.

Aam Aadmi Rising - Politics and Possibilities

AAP might have lost this particular election, but they are showing how they can win the larger game. The fact that the party is only a year old and this was their debut in Indian politics, makes their story shine above every other election victory this season.

The AAP was founded in November 2012, following an ideological debate between Kejriwal, Hazare and their supporters after the Jan Lokpal agitation of 2011. At the start of the movement, the duo had aroused the public with their rejection of politics, only for Kejriwal to break off from Hazare, eventually choosing politics as a legitimate way to effect change.

As a new entrant in an established political space like Delhi, AAP was contending against India's biggest national parties, the Congress and the BJP. The fledgling was up against the 15 year old incumbent government of three consecutive terms, which has built Delhi's infrastructure to much of the high class standards that it has today. Kejriwal decided to contest the New Delhi constituency, because he wanted to take on Delhi's Chief Minister Sheila Dikshit, on her own ground.

Political analysts called that a big mistake, saying he should have contested a seat where he was "more likely" to win, so that he could at least get his foot in the door of the assembly, but he proved them wrong.

AAP was also taking on the BJP with its star candidate Narendra Modi having campaigned for his party in several rallies across Delhi in the months leading to the elections. The BJP has been running its campaigns on actively pushed claims of economic development in BJP states, especially Gujarat, and during their brief tenure at the centre. AAP had no past performance of development to back its manifesto's aims, and had only idealistic intent and passion to show.

The BJP contends that it won because of its development agenda and track record, but the fact that AAP managed to get nearly as many seats as they did and deny them a clear victory means that the BJP is up against almost as many people who don't buy its ideology as those who do. Such close matrices bring no security.

AAP has managed other feats as well. If this Delhi Assembly stands, there will be only three women legislators, and they all belong to the AAP. This is in a place where 53 lakh women and 66 lakh men are registered voters. Shazia Ilmi, one of AAP's prominent women candidates spoke on the need to create space for a gender-politics. This brings the other shift that AAP is trying to effect - the thrust on issue based politics as opposed to caste, religion and money which are tools of exploitation in Indian politics for ages.

Another rooted plague in Indian politics is the presence of politicians well past their primes, who never leave their seats, and the absence of young blood due to apathy or claustrophobia induced by the old guard. All the 28 candidates from AAP who won legislative seats are first time legislators.

While the other four states to which elections were held are now moving on to set up new governments, Delhi continues to wait for a Chief Minister.

What has changed for certain and will hopefully remain, irrespective of who finally retains power, is the focus on cleanliness in personal and democratic

politics. If AAP can retain its current strength and grow in it, its presence is likely to create a peer pressure, where new and old parties are forced to clean

their parties of criminals and under-performing members. Its stubborn insistence on not siding with those they term corrupt parties, even at the risk of not being

in power this time, sets the bar high for other parties to follow suit and for voters to demand such politics.