Although National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data confirm an appalling 1.5 lakh farm suicides between 1997 and 2005, the figure is probably much higher. Worse, the farmers' suicide rate (FSR) - number of suicides per 100,000 farmers - is also likely to be much higher than the disturbing 12.9 thrown up in the 2001 Census.

In the five years from 1997 to 2001, there were 78,737 farm suicides recorded in the country. On average, around 15,747 each year. But in just the next four years 2002-05, there were 70,507. Or a yearly average of 17,627 farm suicides. That is a rise of nearly 1,900 in the yearly averages of the two periods. Simply put, farm suicides have shot up after 2001 with the agrarian crisis biting deeper.

A comprehensive study of official data on farm suicides by K. Nagaraj of the Madras Institute of Development Studies (MIDS) pins down these and other figures. The data analysed by Professor Nagaraj are drawn from the various issues of Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India, a publication of the NCRB. But Professor Nagaraj also explains some of the reasons why the actual numbers and farmers' suicide rate (FSR) could be far higher.

In 2001, when the farm suicides were not yet at their worst, the FSR at 12.9 was already higher than the General Suicide Rate (GSR) - suicides per 100,000 population at 10.6. But even this higher suicide rate among farmers conceals a far worse reality. Firstly, the NCRB data seem to underestimate the number of farm suicides. This is because the criteria adopted for identifying a farm suicide at the State level are quite stringent. For instance, women and tenant farmers tend to get excluded from lists of farmers' suicides. In those lists, only those with a title to land tend to be counted as farmers. On the other hand, the Census data are based on a very liberal definition of 'cultivator.'

Categories of cultivators

The 2001 Census gives data on two categories of cultivators: Cultivators among 'main workers' and those among 'marginal workers.' For the first group - cultivators among main workers - farming is the main activity. The second group includes those who practice cultivation only on a sporadic basis. However, both groups get counted as farmers. The net result of this is that while deriving the farm suicide rate from the NCRB and Census data, we are saddled with figures that undercount farm suicides but overcount the number of 'farmers.' Hence a value of 12.9 for the FSR is likely to be way below the mark. As Professor Nagaraj points out, "If we took only the cultivators among the main workers as farmers, the FSR increases dramatically to 15.8 which is nearly one and a half times the GSR of 10.6 in 2001."

Secondly, the FSR is anchored in 2001 because that is the year of the Census. However, it was not one of the worst years in terms of farm suicides. Farm suicides in that year actually fell when compared to the previous year, 2000. But the very next year, in 2002, farmers' suicides leapt by about 10 per cent. And the number of such deaths peaked in 2004. So while the number of farmers' suicides shows a rising trend after 2001, the number of farmers may well have declined.

The trend of a decline in cultivators seems to have begun even earlier. The 1991 Census says there were 111 million cultivators among main workers. This fell to 103 million in the 2001 Census. This decline would surely have sharpened after 2001 as the farm crisis deepened. Certainly farming has no new takers.

As Professor Nagaraj's study shows, the Annual Compound Growth rate (ACGR) for all suicides in India over the nine-year period 1997-2005 is 2.18 per cent. This is not very much higher than the population growth rate. For farm suicides, it is much higher, at nearly 3 (or 2.91) per cent. An ACGR of 3 per cent in farm suicides is more alarming as it applies to a smaller total of farmers each year. This means the farm suicide rate must have shot up after 2001.

•

1.5 lakh farm suicides in 9 years

•

Maharashtra: Graveyard of farmers

•

One suicide every 30 minutes

Huge differentials in numbers

Lastly, whether we take the farm suicide rate as 12.9 or 15.8, it is the figure for the country as a whole. That again hides huge differentials in the numbers and intensity of farm suicides across the country. There are States and regions in the country where the FSR is appallingly high. There are regions where it is mercifully still low.

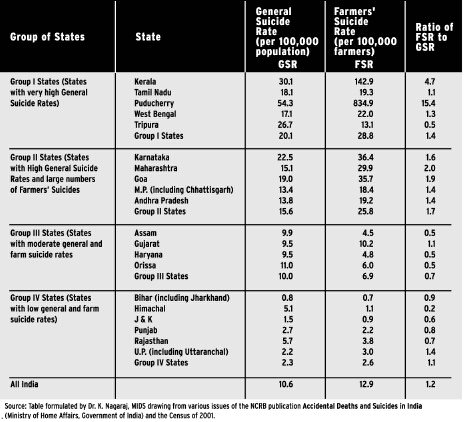

Professor Nagaraj accordingly divided the States into four groups. Group I: States with very high general suicide rates. Group II: States with high general suicide rates and large numbers of farmers' suicides. (This is the most important group.) Group 3: States with moderate general and farm suicide rates. And Group 4: States with low general and farm suicide rates (See Table).

What demarcates the Group II States - clearly the worst hit - is also the trend in suicides, which is most dismal there. This key group includes Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Madhya Pradesh (including Chhattisgarh) and Goa. (The last with tiny absolute numbers.) The ratio of farmers' suicide rate to the general suicide rate was highest in this Group (see Table). The overall ratio of this group is 1.7. Which means the farm suicide rate in these States is 70 per cent higher than it is in their whole population.

Of the major States, Maharashtra has the worst figure with a ratio of farmers' suicide rate to general suicide rate of 2.0. That is, one hundred per cent higher. This is followed by Karnataka with 1.6. Of the smaller States, Kerala (from Group I) has the awful figure of 4.7. But it also shows a decline from 2004. Puducherry shows up as the worst with 15.4. Of course, the last two have smaller absolute numbers.

The trend for Group II is most dismal. The AGCR for farm suicides in these States for the 1997-2005 period was 5.33. Or nearly double the national figure of 2.9. And if this trend holds, farm suicides in this group as a whole would double every 13 years. Among these States, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh would fare even worse.