On average, one Indian farmer committed suicide every 32 minutes between 1997 and 2005. Since 2002, that has become one suicide every 30 minutes. However, the frequency at which farmers take their lives in any region smaller than the country - say a single State or group of States - has to be lower. Because the number of suicides in any such region would be less than the total for the country as a whole in any year. Yet, the frequency at which farmers are killing themselves in many regions is appalling.

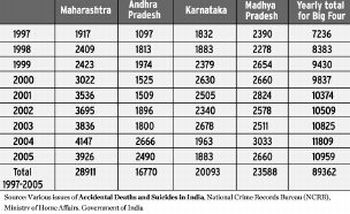

On average, one farmer took his or her life every 53 minutes between 1997 and 2005 in just the States of Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh (including Chhattisgarh). In Maharashtra alone, that was one suicide every three hours. It got even worse after 2001. It rose to one farm suicide every 48 minutes in these Big Four States, and one every two and a quarter hours in Maharashtra alone. The Big Four have together seen 89,362 farmers' suicides between 1997 and 2005, or 44,102 between 2002 and 2005.

K. Nagaraj of the Madras Institute of Development Studies (MIDS), who has studied farmers' suicides between 1997-2005 based on the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data, divides the States into four groups. The worst of these is Group II which includes, besides the Big Four, the State of Goa which shows a high farmers' suicide rate (FSR) - that is, suicides per 1,00,000 farmers. However, Goa's rate is based on tiny absolute numbers. All Group II States have high general suicide rates (GSR) - suicides per 1,00,000 population - and have seen large numbers of farm suicides.

Of these, Andhra Pradesh shows some decline in 2005. And the government claims the numbers have fallen further in 2006. But there is no NCRB data to support this as yet. In all, if the NCRB data are valid, then Andhra Pradesh saw 16,770 suicides between 1997 and 2005.

Decline in Andhra Pradesh

Andhra Pradesh was the first State after the 2004 polls to appoint a commission to go into the agrarian crisis. Based on the commission's advice, it also took some steps towards handling that crisis. It restored compensation for the suicides that had been stopped by the previous regime in 1998. It persuaded creditors to accept a one-time settlement of debt in several cases. This possibly helped see a decline after the terrible years of 2002-04. However, Andhra Pradesh has begun to mimic Maharashtra in one unhappy aspect. The number of 'non-genuine' cases - those the government does not accept as distress-linked - keeps mounting each month while the 'genuine' suicides decline.

There are other problems too. Several States, notably Maharashtra, have made identification of farmers' suicides extremely difficult by using indicators that rule out vast numbers from being categorised as such. One problem with such corruption of data is that it will eventually reflect in and distort future NCRB reports as well.

Karnataka too records some decline in 2004 and 2005, after a disastrous five-year period. And the State's 15 per cent increase in non-farmers committing suicide in the 1997-2005 period is five times higher than the rise in farmers' suicides (3 per cent). But the damage of those earlier years was huge. Karnataka saw as many as 20,093 farm suicides in the period. Again, it is unclear whether the lower numbers for 2004-05 were largely due to policy measures or whether there have been new and creative accounting techniques.

"Madhya Pradesh appears to have long been a problem State for farmers, though this has not been so far acknowledged," says Professor Nagaraj. "The increase in farm suicides over the nine-year period 1997-2005 is not so high, at 11 per cent, but the absolute numbers have been very high for a long period. Much higher than in many other States. However, here too, the rise in non-farmer suicides, at 48 per cent, is more than four times the increase in farmers' suicides." Madhya Pradesh (including Chhattisgarh) saw 23,588 farm suicides in the 1997-2005 period. However, Madhya Pradesh has mostly escaped the media radar as a farm crisis State. In Group II States, farm suicides as a percentage of total suicides reached 21.9 in 2005 against a national average of 15.5. In short, more than one of every five persons taking his or her life in these States that year was a farmer. Also, one in every four suicides in this group was committed using pesticide.

•

1.5 lakh farm suicides in 9 years

•

Suicides worse after 2001

•

Maharashtra: Graveyard of farmers

Kerala created a 'Debt Relief Commission' soon after the change in government there in 2005. The Commission held a case by case scrutiny of the debt problem, while the government halted aggressive loan recovery measures by banks and money lenders. On the Commission's advice, the government also decided to declare the entire Wayanad revenue district distress-affected.

Kerala still vulnerable

The improvement is quite fragile and could easily see a downturn. Kerala's farm suicide rate for the period is very high, and the State remains vulnerable to volatility in the prices of, for instance, coffee, pepper, cardamom or vanilla. A fragility enhanced by the fact that major relief on the debt front requires Central help. Besides, State bureaucracies are extremely hostile to debt relief for farmers. Also, India's free trade agreements with nations and neighbours that produce the same cash crops as Kerala hurts badly. The State's balance on the farm suicides front is very delicate. Complacence would be, literally, fatal.

Group I States are those which have very high general suicide rates. That includes Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Puducherry, West Bengal, and Tripura. "However, Group I's share of both total suicides and of farmers' suicides declined between 1997 and 2005, even as that of Group II steadily rose," points out Professor Nagaraj.

Group III States (Assam, Orissa, Gujarat, and Haryana) are those which have 'moderate general and farm suicide rates,' while Group IV States (Bihar including Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh including Uttaranchal, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab and Rajasthan) report 'low general and farmers' suicides rates.'

Generally speaking, the Gangetic plain region and eastern India have seen fewer farm suicides. States such as Uttar Pradesh (including Uttaranchal), Bihar (including Jharkhand) and Orissa report very few suicides of this kind. These States are in many respects the opposite of the Group II or 'Suicide SEZ' States. These are overwhelmingly food crop regions. They are not intensive input zones, and their costs of cultivation are much lower. Use of chemicals is not anywhere at the levels it is in the Group II States. Government support prices for food crop provide some minimal stability. And there is obviously a better water situation.

States such as Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan and Gujarat also report few farm suicides but their data have been challenged. Haryana, for instance, reports fewer suicides but its increase over the nine-year period was 211 per cent. This springs not from the recording of huge increases in recent years, but because the base year data appear highly flawed. For 1997, Haryana reports a spectacularly low 45 suicides. Which distorts the figure of increase in farm suicides across the period, pushing it upwards. "It could just have been that the counting operation was really shoddy or that it collapsed or was incomplete when data were sent in 1997," says Professor Nagaraj. The numbers after the low 1997 figure remain roughly within a 170-210 range each year. Which again is strongly contested by farm unions and activists.

There are peculiar indications in Gujarat. Pesticide suicides - a common tool in farm suicides - are 84 per cent higher here than farm suicides. At the national level, they are just 28 per cent higher. Why is the gap three times bigger for Gujarat? Even for Group II States, pesticide suicides are only 21 per cent higher than farm suicides. Which raises the question whether several deaths in Gujarat ended up being recorded as just 'pesticide suicides' without being acknowledged as suicides by farmers.