Janki, a slumdweller from Delhi's Ekta Vihar, addressed an attentive audience: "I bought no rations from January to April this year (2004), as you can see from the blank sheets in my ration card. The shopkeeper's records show I took wheat and rice during these months. He has cash memos against my name, bearing signatures of people I don't even know! He made false signatures and sold off the rations to other people at high rates."

Phulaya, Susheela Tiwari and several other residents from Delhi's Ekta Vihar and Jagdamba Colony related similar experiences at the recent public hearing in Delhi on the `Public Distribution System (PDS) and the Right to Information', held during the second National Convention on the Right to Information.

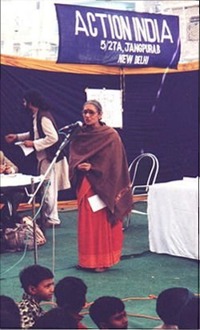

![]() Aruna Roy at a jun sunwai (public hearing) in Delhi (Picture: Stefan Mentschel)

Aruna Roy at a jun sunwai (public hearing) in Delhi (Picture: Stefan Mentschel)

The convention (held from October 8-10) attracted well over 1,000 participants from more than 20 Indian states. Many participants spoke of how they were not able to access the PDS in their state. Revathi and Gomti Mugri from Bolangir (Orissa) said tribals in their area had no ration cards despite intense poverty and severe malnourishment.

Walsingh and Kacharsingh (Bhilala adivasis from Badwani, Madhya Pradesh) spoke of severe drought, famine and unemployment in their region; those who have ration cards do not have the money to buy even subsidised rations. Kacharsingh said: "Wheat is sold to us at Rs 5 per kg, but sold to multi-national companies (MNCs) at Rs 3 or 4 per kg. We want to know under which law this is done." A few participants also talked about how they used the Right to Information Act in their states to expose corruption in the PDS.

The demand for people's Right to Information (RTI) first emerged in Rajasthan in the context of Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan's (MKSS) grassroots work on the issue of minimum wages. Throughout the early 1990s, MKSS activists and ordinary villagers tried to access information on local developmental expenditure. Time and again, they discovered glaring discrepancies in official records. The organisation evolved a uniquely effective method of dealing with the situation: social audit through jan sunvais (public hearings).

The first jan sunvais were held in the mid-1990s, in Pali, Rajsamand, Ajmer and Bhilwara districts of southern Rajasthan. Villagers compared the records with the reality on the ground. Panchayati Raj functionaries and government officials were invited to the jan sunvais at which affected villagers presented the facts in a public gathering. The results were stunning. At the jan sunvai in Janawar (in 2000), massive misappropriation of funds, sanctioned for a school, roads, channels and other public works, was unearthed: the amount misappropriated being Rs 4.5 million out of a total sanction of Rs 6.5 million.

Aruna Roy of MKSS (winner of the Ramon Magasaysay Award in 2000 for Community Leadership) noted, "The State is accountable to its citizens; but if there is no transparency, people don't know exactly what is happening and cannot exercise their basic democratic rights. RTI is a tool to begin making democracy a reality."

In recent years, people's groups across the country have used RTI in diverse forums. Simultaneously, the groups have fought for a new law to ensure that ordinary citizens can access relevant official records. The Right to Information Act was passed in Tamil Nadu in 1996, Goa (1997), Rajasthan (2000), Maharashtra (2000), Karnataka (2000), Delhi (2001), Madhya Pradesh (2003), Assam (2004) and Jammu and Kashmir (2004).

The first national convention on RTI was held at Beawar (Rajasthan) in 2001 to share and consolidate experiences from across the country. Responding to growing pressure, the Indian Parliament passed a Freedom of Information Bill (FIB) in 2002. However, the Bill has not yet been notified - a pre-requisite for it to become law.

Participants at the second national convention noted that the national-level FIB suffers from many limitations and would not be effective unless several loopholes are plugged. The United Progressive Alliance government has promised to amend and pass the Bill as part of its Common Minimum Programme. Proposed amendments include extending the definition of `information' beyond administration, and include government and governmental institutions, defence and police.

Further, information should be made accessible at various levels, including the block and panchayat (village council) level. Only a reasonable fee should be charged for providing information; and reasons for denying information should be clearly specified. Many people also think the Act should have more teeth in order to be effective. Failure to provide information should be a cognisable offence with suitable punishment.

• Officials resisting amending RTI law

• Assertive citizenship taking root

P V Rajagopal of Ekta Parishad, an NGO working on land rights, said that besides fighting corruption, the Act can be used to prevent MNCs from taking over tribal land: "In Madhya Pradesh and Chattisgarh, tribals are being forced to sell their land for `development'. The new trend of corporate farming is pushing communities further towards hunger and pauperisation. These communities can use RTI as a tool to question many of the decisions leading to this situation."

Suman Sahay of Gene Campaign, an NGO, urged that the Act be used to keep asking questions relevant to India's primarily agricultural society: `What do pesticides contain?', `Why are we being sold terminator seeds?' and so on. Jean Dreze, well-known economist, said the Act could be used in struggles to ensure rights to employment, food, anganwadis (village child care centres) and land reforms.

MKSS's Shankar Singh warned: "There is a mafia functioning, whether it is around PDS, developmental expenditures or any other area of public life. We have to confront this whenever we take up such issues. The powerful nexus of interests starts threatening people whenever they demand relevant information." The fact is that resistance to the RTI Act is bound to grow as it engenders and supports further struggles challenging entrenched power structures.

Workshops were held at the convention on a range of relevant issues and their linkages with Panchayati Raj Institutions - including forest rights, right to work, environmental pollution, nuclear arsenal, criminal justice system, police atrocities, urban evictions, land rights, education, health, disabilities, and water and food security. Vigorous participation by rural and urban activists as well as some academicians, lawyers and journalists made this a vibrant, fruitful process.

The movement for RTI is, at root, a common person's fight for fundamental rights: the right to life and livelihood, integrity and dignity. It provides hope for the future. All is not lost - we are still engaged in the right fight. (Women's Feature Service)