A sustained campaign of bringing electricity to the villages has succeeded in putting the wires in place. But there are still large gaps in actual access to energy. Why is that, and what needs to change? In this interview, journalist Omair Ahmad speaks with Dr Debajit Palit, Director - Rural Energy and Livelihoods at The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI). Dr Palit's work at the institute since 1998 has spanned a number of aspects of renewable energy technologies - design and implementation, resource assessment and energy planning, clean energy and rural electrification policy and regulation, and more.

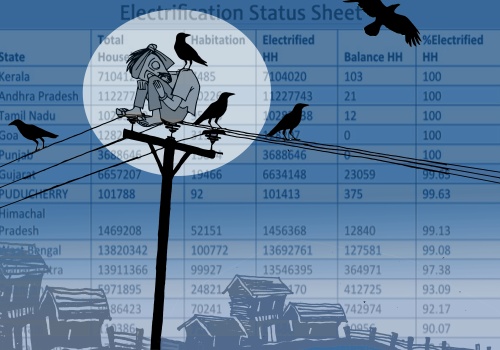

Q. We claim to have electrified all our villages, but many people in rural areas have intermittent access to electricity, if at all. What is the real picture of how many have uninterrupted, regular supply of electricity?

There are four facets to electricity access. The first is extending connectivity to all villages. The second is to connect each household in the village. The third is to provide reliable, round-the-clock electricity along these connections, and the fourth is to make sure there is a responsive service network that takes care of metering, billing, collection, problems, and maintenance.

We have done very well on the first since 2005. At that time around 80% villages had connectivity and less than 50% of households had connections. The passage of the Electricity Act in 2003 made the Central Government also responsible for extending electricity supply along with state governments. This policy has remained unchanged under all governments so far. After the National Rural Electrification Programme was launched in 2005, we made rapid progress, with around 108,000 completely un-electrified villages connected in 8 years or so.

Picture: Dr Debajit Palit.

Picture: Dr Debajit Palit.

At TERI we evaluated this connectivity, and found that often not many households in these villages were being connected, though. Connections to Below Poverty Line (BPL) families were free, but at times it was difficult to tell who was really BPL versus Above Poverty Line (APL). APL families often did not take connections. Maybe they were not sure of the electricity supply, or its sustainability. In which case they would have the bill and little else.

By 2014 all except around 20,000 villages in remote areas were covered, and this was done quickly. This sometimes required decentralised solutions, like solar microgrids or solar home systems. In 2017 the Saubhagya Scheme was launched, and in 18-20 months roughly 30 million households were connected, aiming at the second aspect. There are about 500,000-1,000,000 households not connected. These are either those reluctant to get connections, or are of homes far outside the revenue villages.

In twenty years, we achieved near universal electrification. This was a huge achievement, and is globally recognised. In 2005-06 25% of the global un-electrified, or 400 million people, lived in India. Since then, we have provided electricity access to around 600 million (keeping in mind population growth).

Q. What are the challenges that remain?

The key problem is what happens between the 11 kV feeder to the household. This is where the link breaks down from the government-built high tension wires to the local village. In some ways the question of centralised or decentralised power generation is irrelevant if local service mechanisms do not work. It does not matter if the electricity is coming from the main grid, or from a locally set up mini grid if the Division or the subdivision office is unresponsive and technicians are unavailable.

There are examples where it can work. The Chhattisgarh state government set up mini grids, but their real achievement has been prompt after-sales service. In villages, people are often unable to go the long distance to petition subdivision or division level officials. They often do not know how to navigate the bureaucracy. It costs them time, and that time is costly, because normally they would have used it to work and earn their living.

Q. Would “sweat equity”, for example with locals working to maintain micro-hydro projects in remote hilly areas, or maintain solar projects, help?

To an extent. The government had a franchisee-based electricity distribution policy that it put in place. This could be anything like users’ associations, self-help groups, or local entrepreneurs. They would buy electricity in bulk from the utility and sell to customers (within a price range set by regulators). They would have a 10-15% margin, and it was an excellent business model. We surveyed this in Assam, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Uttarakhand and other states in 2008-11. Services were being provided, and there was increase in collection efficiency and most importantly a high level of consumer satisfaction. It is in the interest of the electricity distribution utilities to improve the customer service delivery through local organisations like franchisees and generate enough revenues (through improved billing and collection efficiencies and reduced distribution losses) to invest in infrastructure improvements.

Unfortunately, this was discontinued in most places. Some state governments complained of the arrangement. Now the only thing that happens in many states is that meter reading and billing are outsourced. These have done little in the way of increasing earnings or reducing technical losses. More importantly the people have no ability to deal with issues that arise. They cannot fix or maintain things, and if there are problems with service, they can do nothing. The centralisation of delivery helps nobody.

Q. Are there other ways that people can be incentivised to be part of the solution, like selling electricity to the grid?

This is part of the PM KUSUM scheme, which supplies solar panels to farmers for the use of water pumps and other essentials. There is the option of selling the power to the grid if they have excess electricity. Unfortunately, there is a real problem with the finances of most distribution utilities. They may not be in a position to buy this electricity.

|

|

Solar power in urban areas has a different, though related, problem. The people and organisations, who can afford to set up solar panels, and potentially sell power back, are the creamy consumers. If they are out of the grid, who will subsidise the electricity rates for the poorer consumers?

We need to think of finances, maybe create a fund that can manage these financial difficulties. But because electricity is a concurrent subject in the Constitution, this will require states and the Centre working together, and that is sometimes challenging.

Q. Are we going to meet our renewable goals as we expand our electrification programme?

That should actually be easy, if present trends continue. Over the last few years, we have largely only been adding renewable energy to the grid. There have been few, if any, new coal plants. The one main challenge is storage price, and by 2030 this should also be cost effective. Renewable energy just makes good financial sense at this point of time.

Q. Is there something we are missing?

Robust data. We do not have enough monitoring to build a realistic model of what is happening and why, or to evaluate the health of the network. You can install a prepaid smart meter and that tells you what is happening in the home, but not what is happening between the 11kV line to the household, the state of the transformer and the LT network, the last link. Electricity given free in rural areas to farmers is not metered, we don’t know what is happening there. We just cannot plan properly with big parts of the data missing.

A second thing is a focus on change management, especially in distribution companies. We put in reforms, and these are top down. As someone in such a utility remarked, what is the incentive for him to change how he works? This means that these reforms remain superficial. In the late 90s when we did a lot of electricity reform, we backed this with change-management training that helped people working in these companies understand that the changes were to their benefit. Even when Gujarat undertook similar changes, many of which were also included in the UDAY scheme launched in 2015, it was accompanied by a great deal of training.

Without that, it is hard to convince people. Our problem remains centralisation of delivery and services, and a lack of engagement with the people – whether in distribution companies or those they serve.