The Comprehensive Household Survey conducted by the Government of Telangana State on a single day on Tuesday, 19 August to cover the entire 84 lakh households as estimated by Census 2011, has turned out to be a resounding success, despite several fears, apprehensions and valid criticisms.

Interestingly, the Survey has exposed the poor quality of existing data, even provided by the Census, as it showed that there are more than 1.05 crore households in the state, at least 21 lakh more than in 2011, a highly improbable increase in three years. The government is yet to announce the findings officially, but initial reports from district collectors and other concerned officials point towards these figures.

The idea of the survey is not new for governments in India and there might have been similar exercises over the decades, particularly to identify the target beneficiaries when conceptualizing or implementing welfare schemes. However, the current survey has become controversial and provoked a lot of criticism and widespread fears and rumors.

The fears and apprehensions were spread by a range of forces, with all kinds of intentions. First, there were the political parties, which usually take an off-tangent position to any government initiative; the BJP, TDP and Congress in particular expressed their reservations and criticism of the survey, its procedure and probable motives.

Added to their opposition was the motivated criticism from forces that wanted to retain Andhra Pradesh united, those in favour of the rich and powerful of coastal Andhra and Rayalaseema, bent on continuing their stranglehold on Telangana.

Another stream that fed and strengthened the rumours and apprehension came from the media - both Telugu media, because of their management policy and English, because of lack of information.

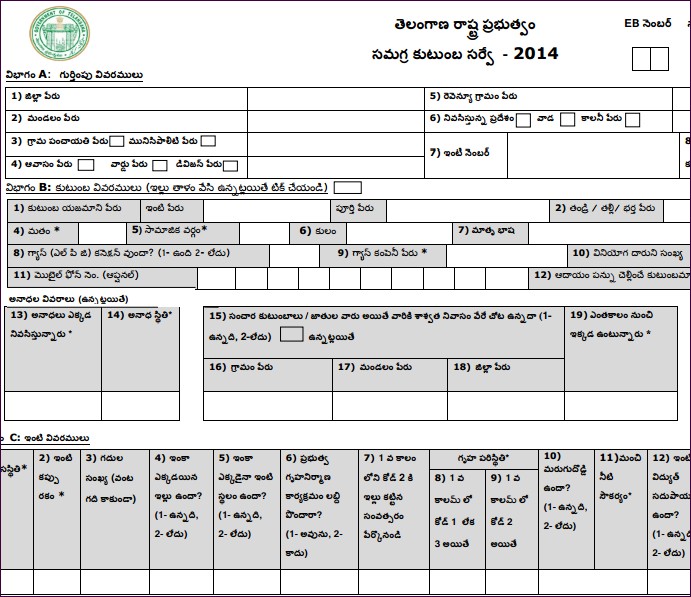

A partial snapshot of the Family Survey form

The fears that were put forth included “ethnic cleansing”, “identification of migrants” and “special targeting of migrants from Andhra and Rayalaseema”. Even though reams and reams have been written and hundreds of hours of sound and visual bites were spent to dispel these, many knowledgeable commentators filled their columns in English media based on these fears, the actual schedules did not have any such questions.

In reality, the roots of this controversy lay in another equally contentious proposal. The government wanted to do away with a welfare scheme-turned-scandal involving Rs 4000 crore per annum, called fee-reimbursement for higher studies.

The scheme, launched during Y S Rajasekhar Reddy’s regime and meant to provide for ‘Fee Re-imbursement for post-matric higher education’ of SC, ST, BC and economically weaker sections, had become a cash cow for private educational institutions, involving all kinds of racketeering.

It is believed that fewer Telangana students than their Andhra and Rayalaseema counterparts were beneficiaries of this, and the new government introduced a new scheme called Financial Assistance to Telangana Students (FAST). In the ensuing debate, authorities said that the government would like to provide assistance to natives of Telangana alone and that stirred a hornet’s nest.

The Comprehensive Household Survey began in this shadow and given the context, people feared that the survey might be aimed at determining nativity. Interested parties fomented these fears.

The government tried to refute these rumours and apprehensions but the effort could not match the adversaries’ and the government’s insistence fuelled the rumours.

In reality as it transpired, the migration aspect, which is incidentally a common question in the Census exercise as well, did not even figure in the current survey. Not even a single entry in the four-page schedule reveals the respondent’s nativity, his so-called “ethnic” identity or “permanent residence” which is the norm in any standard survey.

What was the survey for?

But if these fears were indeed unfounded, then why did the government initiate this exercise at all? The first indication of the survey came with the chief minister K Chandrasekhar Rao’s announcement on 1 August, three weeks prior to the survey. On that day, at a meeting with revenue officials drawn from all over the state, he said the quality of data in the state is ‘lackadaisical’ and the government needs foolproof data to be able to implement its welfare schemes and to reach the targeted sections exactly. The survey also aimed at weeding out the ‘ineligible’ and ‘bogus’ beneficiaries of various government schemes.

“People have high expectations from the government. To meet their expectations, we have to have accurate figures to work out various welfare initiatives and developmental programmes. In that direction, we have decided to take up the ambitious Intensive Household Survey 2014,” he said at the meeting.

As an example of the loopholes in the existing data, the chief minister compared the Census figure of 84 lakh households with the 91 lakh white ration cards and 15 lakh pink cards issued in the state. The white ration card enables a household to get subsidised essential commodities from Public Distribution System and by definition, has to be given to Below Poverty Line families.

It entails several other welfare benefits like fee-reimbursement and health schemes. But ironically there were at least 7 lakh more white cards than the total number of households, indicating that the entire state, or more than that, was BPL!

Thus, the Telangana Rashtra Samithi had a strong basis for its hopes on the survey in terms of its ability to weed out bogus cards, collecting data for implementation of targeted pro-people welfare schemes and plugging loopholes and leakages. However, though the survey could be commended for its intentions, there have been some valid criticisms, both from the “hidden agenda” perspective as well as its procedural aspects.

Was a survey really necessary?

If weeding out excessive white ration cards is the primary objective, there are alternative methods to do that. The issuance of bogus cards is the handiwork of politicians, ration shop dealers, illegal marketers of subsidised commodities, with the active connivance of government officials in the concerned departments. If the government is sincere enough, these four sections of culprits can be easily checked and that would have been an easier task than sending out four lakh employees to 84 lakh households, in a virtual shut-down situation.

Indeed, Census schedules contain almost all the details that the current survey is seeking to collect. Other government agencies like NSSO, NIC, Planning Commission, etc also have such data and the state government could have easily collected whatever information it needed.

In fact, this also weakens the genuine concerns of security of data and protection of privacy, given that the data on almost all the mandatory entries is already in the public domain with some state or non-state data collection agencies.

The government, however, seemed to create an impression that this was an innovative, first of its kind exercise to gather faultless data. This claim has led to bitter criticism - some of which may be motivated - on the one hand, and unabashed praise, almost bordering on sycophancy, on the other.

If the survey results are going to be used as a multi-purpose vehicle in future, it is valid but then the question remains whether the same government employees get foolproof data which they could not get earlier. It is also true that these government officials have developed a vested interest in producing and conserving poor data.

Moreover one needs to keep in mind that the government itself clarified that disclosure would be voluntary. This assertion followed a petition seeking a stay on the survey, filed by an advocate Seeta Lakshmi and a citizen Tulasi Rajasekhar. The High Court heard the case and during the proceedings, Advocate-general K. Ramakrishna Reddy told the court on behalf of the state government that participating in the survey was voluntary and that no one would be pressured to participate.

The High Court disallowed the stay petition and gave a go-ahead. Even after that, another advocate P V Krishnaiah filed a Public Interest Litigation saying that the survey was illegal as there was no government order to that effect. The High Court, still refusing to stay the survey, gave notice to the government.

The survey was finally scheduled for August 19, which the government declared a holiday. It asked everybody to stay at home. The two days prior to it were earmarked as pre-survey days, when a model single page sheet and a check list were supplied to each household. Thanks to yet another rumours that ration cards of those who did not participate may be cancelled, people stayed home, ready with photocopies of all their documents. The roads wore a deserted look as there was remarkable response and participation from the people.

However, either because of lack of proper training or merely lethargy, most of the enumerators did not ask too many questions, except some mandatory ones, and allowed households to give voluntary information, as the government had already assured in court. Though it was thought that all the members of a household should be present before the enumerator when the responses were being recorded, even a single member was allowed to give the details of others.

While it was rumoured that the enumerators would check each room to verify household properties, in most of the places the enumerators completed their job at one site, most often in the drawing room alone. In fact, in some areas, people from different families assembled at one place to give the details.

The crucial question, therefore, is what kind of analysis would be possible with the bits and pieces of information collected thus. Where so many columns were left unanswered, how would the computers or compilers arrive at usable datasets?

Given the experience of the Chandrababu Naidu and Rajasekhara Reddy regimes and the insistence of the World Bank on conducting surveys for any government initiative, the current government may also use the survey results as a pretext or alibi for anything it wants to do, irrespective of whether the data is available or not.

At the end of the day, more heat has been generated than light and one has to see at whom the heat will be eventually targeted.