National and multinational electronic and electrical companies in India are violating e-waste management norms while regulatory authorities are failing to take action against them, says a report published on 24 June 2014 by Toxics Link, an environmental research and advocacy group based in New Delhi.

Currently, India produces a whopping 2.7 million tons of e-waste every year but there are a handful of 42 e-waste collection units and 55 recycling units registered in the entire country, says the report. A chunk of the e-waste generated is managed by the informal sector, which has been operating illegally, putting humans and environment at great risk.

It was in light of the illegal operations and associated risks that the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India, notified the E-waste (Management and Handling) Rules in 2011 and enforced these a year later in May 2012. A year’s time between notification and enforcement of the rules was meant for companies and regulators to implement the rules and set up an infrastructure for e-waste management.

The report titled ‘Time to Reboot’ now looks at the status of the implementation of E-waste Rules (2011) as revealed by information gathered over the period 2012–2013. “We wanted to check how the two important agencies – the electronic [companies] and the State Pollution Control Boards / Committees – are faring in implementing the rules and how successful they have been [in managing e-waste],” says Priti Mahesh, key researcher of the report and senior programme coordinator at Toxics Link.

Pic: Praveen P/Wikimedia

The report looked at 50 (19 national and 31 multinational) leading companies shortlisted from across the telecom, information technology and consumer goods sectors. Under the E-waste Rules (2011), manufacturers, assemblers and sellers of electronic and electrical products are mandated to set up systems to take back the products from consumers after the products’ end of life, and recycle them in an environmentally safe manner.

The report rated the companies based on their take-back systems, information available to consumers on how to return the products and the number of collection centres in the country. It found that 17 out of 50 companies “have taken no action to fulfil their responsibility under the Rules,” a majority (11) among which are primarily cell phone companies including Blackberry, HTC, Karbonn, Lemon, Maxx, Micromax India, Olive, Xolo and Zen Mobile. Another 15 companies have done little to comply with the rules, the report says.

Rating companies based on their consumer friendliness in taking back e-waste.

Pic: Toxics Link

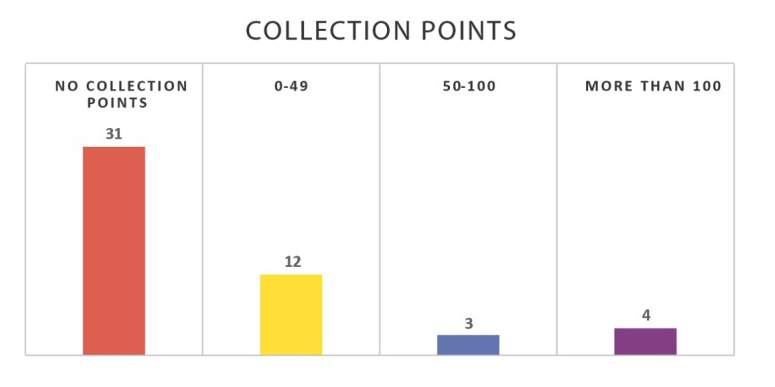

Only seven companies – a mix of national and multinational – were found to have enough information about e-waste management on their websites, a take-back strategy and centres for collecting obsolete products. The remaining 11 stood somewhere in between. Only four companies out of the 50 considered – Canon India, Lenovo, Nokia and Onida – had more than 100 physical collection points or drop-in centres across the country; 31 companies had none.

The number of companies with collection points for taking back ‘end of life’ products.

Pic: Toxics Link

Ineffectual Pollution Control Boards

The regulators – State Pollution Control Boards and Committees – have the right to cancel the authorisation of companies for failing to handle e-waste. In effect, however, “they have been toothless. No action has been taken against the violators,” Priti told India Together.

She and co-researchers pored over the websites of regulatory bodies and found that 13 of the 35 Pollution Control Board and Committee websites had “no information” on e-waste. Only four of the remaining 22 had in-depth information, including a list of recycling facilities, on their websites.

“We [also] sought information through the Right to Information (RTI) Act on what kind of monitoring systems they had created and whether they had e-waste rules clearly specified. We asked them if inventories [of e-waste generated] had been done in their states, how many e-waste processing units there were and how many producers they had [authorised].”

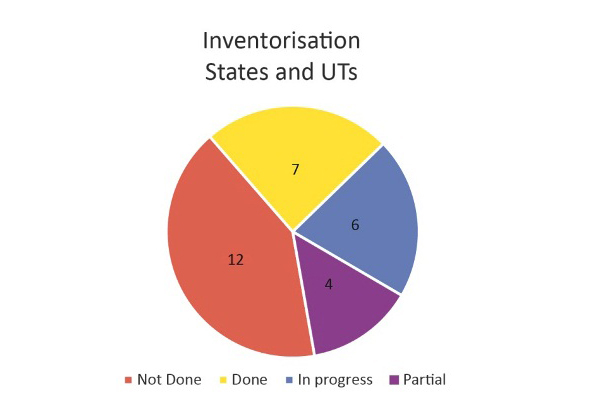

No more than seven states had carried out a thorough analysis of e-waste generated. Of these, West Bengal with 34,124 metric tons and Andhra Pradesh with 4268.42 metric tons were the chief e-waste producers during 2011–2012.

“Probably one of the highest e-waste generating states,” Karnataka, whose capital city Bangalore is an information technology hub, did not have information available on the amount of e-waste generated, according to the report.

Progress made by States and Union Territories in estimating e-waste generated.

Pic: Toxics Link

Considering the dismal performance of the regulators, Priti says the E-waste (Management and Handling) Rules (2011) could do with some changes. Mandating yearly targets for e-waste collection by companies is necessary. The number of e-waste collection centres also needs to be defined for every state, in both urban and rural areas.

“The collection points we see are concentrated in large, urban sectors and the rural areas are mainly neglected. We all know that electronics are getting into rural areas as well.” All pollution control authorities must carry out an inventory of e-waste generated in their respective states, she says.

Besides, the report assessed only 50 national and multinational brands but there are several other local companies assembling or selling electronic and electrical products that were not considered. Priti points out that there is an urgent need for a comprehensive list of companies operating in the country, so that all can be monitored.