India's unorganised sector has seven times greater labour intensity per unit as compared to the organised sector and is some five times less capital intensive. Studies have only reinforced the fact that the majority of workers in the unorganised economy of India have never been to vocational training institutions and/or school. On the other hand, the formal skills training system, because of its educational entry requirements and long duration of courses, is designed to exclude the underprivileged informal sector workers. (See: Part I of this article)

Vocational training could play a key role in bridging the gap. But training needs surrounding the informal sector are a complex, almost vicious web of circumstances for most workers.

Take for instance the case of Seema Farid, living near Nainital. Seema is a 15-year old who looks like a malnourished child, lives and stitches clothes in a dirty, cramped 6 sq.metres-room with her three siblings waiting for her mentally unstable mother to drop in sometime.

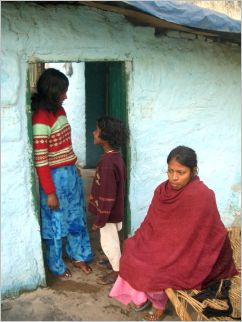

![]() Seema at the far right, with two of her siblings. Pic: Varupi Jain.

Seema at the far right, with two of her siblings. Pic: Varupi Jain.

Seema's father Mohammad Farid passed away when she was ten, leaving her mother Sanara and three younger siblings with no source of income not even the sporadic amounts he could make doing odd jobs around the town. Lack of resources to support her four children left her mother mentally unstable and she started running away from home for a couple of days at a stretch. Gradually the periods she spent away from home grew longer and she came back only once in two months, not even recognising her children the way she did earlier.

It is then that Seema resorted to the help of a neighbour, who had been stitching basic clothes for the slum people. With her help, Seema picked up basic skills and started stitching to feed herself and her siblings. After stitching for two years, she was earning an average of Rs.700-800 per month. This is still way below the 'dollar a day' level. Seema is visibly more aware of her economic prospects or rather the lack of them than others her age. She recognises that stitching the same clothes over and over again might fetch her just enough to sustain her family but does not promise any improvement in her living standard.

Seema had to drop out of school when she was eight. However, she wishes that her siblings attend school. The financial implications of that prospect apart, she simply says that she does not have the ability to do that meaning perhaps that it is beyond her physical capacity to manage and monitor the entire process of sending her siblings to school in addition to what she is already doing earning a livelihood and cooking, feeding and helping her siblings with their daily chores.

This was Seema's situation in 2004 - circumstances which are representative of many informal sector workers at various levels. Some aspects of her situation are evident of challenges that beset vocational training in the informal sector in general:

1. Income generation as an "emergency" option: Many informal sector enterprises micro, small or medium spring out of the dire necessity for income generation. The immediacy of the need to generate income leaves no room and opportunity for an informed decision based on synchronisation of skills, market demands and general business sense.

2. Training takes a backseat: in the above scenario, 'formal' or in fact any kind of marginally regularised training takes a backseat. Training becomes synonymous with improvisation one starts generating income with the skills which are most 'handy' which are either already present or which can be most easily acquired.

3. No avenues for expansion: The entrepreneur usually becomes so preoccupied with sustaining the business at a minimum level that there is hardly any time and energy left for advanced training, linking up with other businesses, thinking of cost-saving and pooling mechanisms, credit facilities and other avenues of expansion of business.

4. No formalisation: The business continues at its present minimum level. Continuation at the present level is itself considered as the best case scenario. There is no business advancement, also no progress towards the formal sector.

The over-arching fact remains that with informal sector groups (as with even the formal sector) one can hardly divorce their economic prospects from their social realities. The majority of them are in their present state of economic deprivation because of reasons deeply enmeshed in their social-economic, at times even religious or cultural settings (especially in the case of women).

While it is true that there are entrepreneurs who deliberately choose to remain informal for the many benefits it brings along in terms of tax benefits and freedom from bureaucratic hassles, there are also people who genuinely lack awareness and guidance towards other alternatives. Take for instance, Rajni Sarohi, a housewife in Nainital who had started and abandoned a home-based garment stitching business. She stopped stitching for the very low rates of return (Rs.500 for part-time work) it brought along for the time and energy she invested. Ask Rajni what she thinks her prospects are and she says, "I could take a loan, but then you should tell me where I should take it from and what I should do with it. You tell me what is best for me. How will I find that out without anyone's help? I already tried once."

Rajni would benefit from what Amit Mitra, writing in an ILO working paper, calls 'training for empowerment'. Mitra writes that it is important to re-conceptualise training and move away from its narrow employment connotation. He points out that training needs to be seen as an input for empowerment, and not just for employment only. In self-help organisations and networks, Mitra writes that learning is not happening in the process of production, but also takes place through other external mechanisms such as negotiation.

In addition, Mitra notes that training for empowerment would need to build up capabilities in people to shift from one profession to another, to obtain the freedom to make choices without losing status. In essence, he writes, what is required is the freedom to grow, to chose a career and develop it.

Mitra's observations directly address the situations of the teenager who works to take care of her siblings as well as the houswife in Nainital. What is desirable is not just undergoing vocational training for income-generation but using training as a means to help the trainee particularly girls and women understand the market and its linkages with producers, suppliers and buyers, their own role and position to generate income and the various possibilities to do so.

Moreover, only training aimed at empowerment, and not 'just' at employment can help poor women given their socio-cultural background identify (which is the first step towards acquiring) the kind of competencies needed to survive adequately and fruitfully in the commercial web. Training for empowerment will equip women to create conditions adequate for survival even when their present employment terminates.

S P Mishra, author of Factors Affecting Women Entrepreneurship in Small and Cottage Industries in India, observes that issues concerning training and operation in the informal sector are even more complex for women simply by virtue of their being women. Women's entrepreneurial abilities are not always approved by their family; workloads are exhausting with the double burden of taking care of the home and family, as well as earning a livelihood; they enter into competition with less knowledge and training than their male counterparts; they have limited access to capital, with many banks doubting their credibility; often they are faced with a limited range of over-competitive occupations; they have to deal with institutional antipathy, where government departments and officials do not give priority to their applications and efforts.

All in all, it is operative to recognise that the training needs and challenges of informal sector workers are far from being uni-dimensional. It is hardly a linear path leading from informality to formality. The challenges are enmeshed within the socio-economic conditions of the groups. Vocational training is one of the aspects along which these challenges can be addressed. What is required is a set of competencies which empowers the workers to make the right entrepreneurial choices. This is even more crucial for women operating in the informal sector.