“Myself, Shilpi Pandey. I am prepare for BHU Mass Communication and Journalism admission (sic),” bubbles the 21-year-old who lives in Sri Ram Vihar Colony in the city of Ballia. Like Pandey, there is at least one member from every family in that mid-sized colony studying English at the branch of what is locally advertised as ‘India’s largest institute of spoken English’. Pandey spent three months -- two hours for five days every week at the institute to fix a lack of confidence and came out convinced that she had finally set out on the path to a bright future, her ‘bright’ being a career in the television industry. “I will do whatever it takes and go wherever I have to,” she says with admirable determination once the conversation has settled into Hindi - a language she is more comfortable with.

The American Institute of English Language. Pic: Roshan Jaiswal

Some 40 kilometres from Pandey’s home, in the village of Medourah Kalan, that dream to make it big has propelled a few members from almost every one of its 500 families to seek a life outside the district which offers few employment opportunities, despite being dotted by some 80 degree colleges. The victim of the Delhi gang rape that happened on December 16, 2012 in Delhi, belonged to one such family.

“When the incident happened, girls were scared to go to college which is 10 kilometres from here. But staying back is not an option. Development has not come to us. There is no future here,” says Paras Nath Yadav, the 40-year-old former pradhan of the village. Yadav’s two brothers live and work elsewhere and he admits that had it not been for an early political initiation, he too would have abandoned the village.

Youngsters at the Institute. Pic: Roshan Jaiswal

Back in Ballia city, Rajeev Kumar, the head of the Political Science department at the Shri Murli Manohar Town PG College sits in his airy, first floor office where a gleaming slim screen computer rests atop a dusty table, and explains that an acute feeling of insecurity is driving migration among the district’s 90 per cent plus rural population.

“Half of those who work as farmers do not own any land. They suffer forced labour and sexual exploitation,” points out Kumar, adding that despite the river (Ganga) changing course, land surveys have not been re-done. Local elites have been permitted a free run in establishing unlawful control over land. Trapped in such dismal circumstances, the low castes migrate with the hope that hard work elsewhere will allow them a chance at a decent life. “In the case of the middle class, it is the spirit to exert which is at work,” he says.

An example of that spirit having outpaced what the district has to offer is served by Kumar’s own work place where the library is in the process of being digitised and the campus is being turned into a Wi-Fi zone despite 10-hour electricity cuts being the norm. Below his office, girls make a beeline to fill in the forms that will make them eligible for the state government’s free laptop scheme (aimed at those who cleared their class 12 examinations last year), but none of those questioned have an answer as to how the machines will work in the absence of power. “That is why I want to get out,” says a science undergraduate who rushes off without giving her name.

Stalls selling job forms are a huge draw for the young. Pic: Roshan Jaiswal

The push factors for migration (for example, lack of employment opportunities) that work so forcefully in Ballia are not unique to it. They spread across Uttar Pradesh, which makes up the largest slice of rural and urban interstate migrations that have contributed to adding approximately 22 million new people to the population of destination cities, of which Delhi remains the most popular.

In 1983, it was to Delhi that Badri Singh, the father of the gang rape victim migrated in search of a better life. Working double shifts as a loader with a private airline and getting less than five hours of sleep every night, he had made peace with the realisation that while the better life would skip him, it would definitely come to his three children.

It is the tantalising possibility of this promise that feeds the migratory stream despite lowly skilled migrants mostly ending up in ghettos and drawing the ire of the original inhabitants of the destination city. The perpetuators of the December 16 crime, also migrants from small towns and villages, were the ugly consequence of a fading of that promise and the resulting economic, social and psychological deprivation.

Yet, with each generation, the illusion of the promise grows more fantastic. “In big cities, it is easier to get returns on your hard work. You are not known for your caste. Your qualification and your job speak for you,” offers 17-year-old Vivek Singh who is a first year student of commerce at a local college. He is aiming for an “MBA with good marks” after which he hopes to find a “manager’s job in a financial company.” His reference point is an uncle who is in the army, not his father who is a teacher.

• Bundelkhand: Living with drought

• Unemployment and migration

![]()

To underscore his point on caste, Singh says that while the whole world was raising its voice in support of the 23-year-old Delhi gang rape victim, in Ballia, she was still defined by her standing in the caste hierarchy. “We took out a candle march and burned some effigies, but there was constant talk about her caste, and about her parent’s failure to control her. Imagine that happening in a big city where factories are well developed,” he asks, connecting economic prosperity with a more inclusive social milieu.

In the course of a day spent in Ballia, this is not the sole disturbing observation on the Delhi gang rape victim. Ramendra Dwivedi, a local journalist says, “There was a muted but palpable sense of resentment that a family of lowly standing had garnered undue attention. The question kya mila (what did the family get?) was of greatest interest. The conflict between big city values and small city aspirations was marked.”

Dwivedi’s observation points to the complicated relationship between migration and acculturation, a relationship burdened by loss, alienation, dislocation and isolation. It hinges on a complicated equation -- clinging to the security of a native identity hawked through culture and caste-based associations while reworking old ties through an economic lens.

Much of the blame for the lack of opportunities lies with the government. In the cause and effect logic of economic activity, the absence of basic infrastructure has turned industry off the region. Thus, while the per capita income of western Uttar Pradesh stands at Rs 15,869, the 21 districts of the state’s eastern region have an income of only Rs 9,288 per person.

Industry experts believe that focussed hard sell can improve the districts’ economy, as the western region is saturated with industries. In the absence of that focus, eastern UP’s income has remained worse than even that of Bundelkhand which, with a per capita income of Rs 12,878, attracts special packages from the centre and the state - a regional anomaly that is explained in part by the more acute nature of distress in Bundelkhand where debt and drought have fuelled rampant farmer suicides and captured political imagination.

The state’s freshly announced ‘New Infrastructure and Industrial Investment Policy, 2012’ which offers 100 per cent exemption in stamp duty and a capital interest subsidy scheme for industries set up in the eastern districts of the state, is yet to yield results. Only the proposed airport at Kushinagar has drawn investor interest for its tourism affecting potential.

More specifically, of the 104 Industrial Entrepreneurs Memoranda, or IEM (initial application for approval to start an industry) filed between April 1, 2012 and January 31, 2013, not a single one proposes an industry for Ballia or for any of the other eastern districts except Varanasi and Sonebhadra. This is in telling contrast to Noida, which has attracted 35 new proposals. Even the 1,047 km Ganga Expressway -- an access controlled eight lane project that was announced in 2007 - to connect Ballia to Noida and thus fuel a more even growth, has been stalled in court.

Ballia’s most recent cause for dissent came from this year’s Railway budget which announced a bi-weekly train to Delhi, but selected its point of origin in Mau (71 kilometres from Ballia), despite representations to the ministry that a train be introduced from Ballia in memory of the bahadur beti (brave daughter), as she is locally referred to.

Krishna Kumar Upadhyay, better known by his moniker ‘Kaptan’ is the convenor of the Purvanchal Vikas Manch, a body which has been demanding statehood for the state’s eastern region. He connects the example of the train to the other slights that are regularly handed to Ballia. “From the inability to procure land to the disinterest of entrepreneurs, from the non feasibility of having a medical university to the administrative logic of not setting up a university there is always a ready answer for why things cannot happen in Ballia,” he says as he prepares to leave for Delhi to press for a route change for the train and demand a 50 per cent reservation quota for Ballia on it.

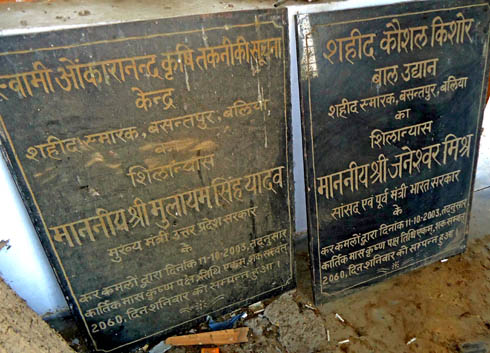

Just 10 kilometres from Ballia, connected by a narrow road that bears a gleaming sign board announcing, ‘Casterbridge School-- Study medium in our school is English’, and sited in the village of Basantpur is a martyrs’ memorial. It was conceived as a showcase tourism project that was to include, among other notables, a Bhojpuri cultural centre and a museum of history spread over 85 acres.

Half a kilometre away is the Surha Taal a pond of mythological medicinal properties that was to be part of the memorial’s charms. Today the memorial is run over by wild grass, the pond choked by mossy overgrowth. Stray paper cups and plastic wrappers that once held namkeens and biscuits are the only reminders of human visitors. Two care takers-- Kunj Bihari and Surendra Nath Barma - roam the grounds listlessly.

The memorial at Basantpur. Pic: Roshan Jaiswal

A little prodding makes them throw open a never-used auditorium with a seating capacity of 213. The red velvet of the seats has started to fade under the plastic covers and the electricity fixtures are falling off. The next stop is a room which houses many of the foundation stones that were laid for the memorial. The earliest, dated 1997, bears former Prime Minister HD Deve Gowda’s name, the last bears the year 2003 and credits Samajwadi Party chief Mulayam Singh Yadav (then the state’s chief minister) with inaugurating an agricultural information technology centre. A third, some distance from the room, is stuck in a red brick wall and announces the inauguration of a wasteland development programme by Ravi Shankar Prasad (then minister for information and broadcasting) in 2003.

Since none of those grand announcements came to fruition, the memorial has been reduced to receiving visitors on Independence and Republic Daystwo dates which hold special significance for the district which by claiming freedom from the British on August 20, 1942 earned the sobriquet Baghi (rebel). Possibly the only time the memorial made news was in 2009, when a private, institute was found to be illegally operating on its premises.

“Things are not pleasant”, despairs Alok Tripathi the founder of the fancifully named ‘Academia para la Educacion Profesional’- a career counselling centre that targets students from Ballia. The inspirational advice on the centre’s web page reads-- ‘If you are not doing for what you are meant, you might not get the amount of success you deserve’ (sic).

Tripathi, who lays claim to a deep desire to change the fate of the district’s youth, is a native of Ballia, and is currently pursuing a doctorate in science from a British university. His original business idea was to prompt students to undertake professional studies alongside regular degree courses, but when he placed the first newspaper advertisement for the scheme, only two phone calls of inquiry resulted. “There is no orientation for private jobs. Parents are unable to guide their children. A government teaching job and the army are the most sought after options. The status of education is such that students do not even know what subjects they are studying,” he says.

Shafique Ahmed, an Assistant Professor in the Gorakhpur University is a specialist in the sociology of development. He links this penchant for government service to an embedded fondness for displays of power and prestige. “An agrarian patriarchy does not demand to know the source of one’s wealth. To be wealthy is the only aspiration. Even a lowly government job ensures that the means to earn that wealth will be found. Social tensions appear because not everyone can have access to those jobs. Livelihoods, culture, political power and a lack of opportunities then begin to clash”, he says.

Lasting resolutions to that clash can perhaps only be found by first altering personal ambitions and then channelling them into the social structure. As did Saurabh Singh, who at the age of 28, found his way back to Ballia, two generations after his grandfather had set out in the 1940s. Singh came on a project to study arsenic contamination in the district’s villages but decided to stay on as he realised that big city living had exhausted his desires. “Life is too fragmented in large cities. Here I can look beyond myself,” he says and describes migration as “a boon in the later stages” when the benefits of education and economics can be poured back into the region of one’s origin.

For Ballia, that later stage is too distant. The dreams of its young are too big. The burden of its past glories is too heavy. And the light of its present too faint, too devoid of hope.