As soon as I got off at Ajmer railway station, I called Bhanvaribai’s mobile phone. In an unsure voice she said, “Since you have come to write about women’s issues, why don’t you come directly to the Ajmeri Gate police station?”

Somewhat astonished, I asked her what had happened. She replied, “Come here and you will find out. We are all 50-year-old women here. You are a young man. They slapped us a few times and sat us down at the police station. So come only if you feel comfortable.”

Bhanvaribai hails from the Ajmer district of Rajasthan. A Dalit woman, she has long been campaigning for the rights of the Dalit community, and especially women within her community. As a journalist, I had travelled to Ajmer to meet her and learn more about the caste and gender equations in this region, which still sports a dominantly feudal structure.

I decided it would be better to go to the police station rather than return to Mumbai. At the police station, the officer-in-charge, Satish Yadav sat behind a table that said “Truth Shall Prevail.” In the backdrop, there was a large framed photograph of Mahatma Gandhi. But Yadav appeared to be far removed from the philosophy that these externalities would imply. He curtly asked who I was, and walked off even before I could say or explain anything.

But what was Bhanvari Bai, who actually belongs to Rasulpura village in the district, doing at the Ajmeri Gate police station in the first place?

Harsh realities of Rasulpura

Rasulpura is hardly 10 kilometres from Ajmer, on the highway to Jaipur. 600 Muslims, 150 Gujjars and 50 Dalits live in the village. In the last few years, 20 Dalit families have had to dump their land and property at throw-away prices and move to Ajmer. The remaining Dalit families also have had to move their houses about half a kilometre from the village, practically living in their fields.

This is the India where Dalits still cannot sit in community gatherings or use water from the village hand pump, and are fearful of riding a bicycle. Members of the Dalit community have to pass through government land to go to their farms. On 6 June 2013, Teja Gujjar dug a trench in this path and placed barbed wire, making it difficult for people to use it. When Bhanvaribai requested a meeting to talk to Teja Gujjar to resolve this issue, he threatened to kill her in the foulest language imaginable.

When the Dalit women approached Teja’s older brother, who is also a member of the village panchayat, saying that they had voted for him and wished he would intervene on their behalf, he suggested sarcastically that they could take the matter to the police if they wished. The fact was that both brothers had been trying to buy out Dalit lands at low prices in a number of neighbouring villages. They hoped that by making life difficult for the Dalit community in the village, they could get them to sell and move.

When the Dalit women approached the police outpost at Nareti, the police said that they would file a case only after investigation. A Dalit constable named Kailash came to the Gujjar brothers to find out what had happened, only to be insulted. The Dalit women then went to Ajmeri Gate police station, which was already unhappy about the numerous Dalit cases registered.

The officer-in-charge is bothered that almost every week three cases of oppression against Dalit women are registered from Rasulpura village. In fact, the official has admittedly attempted to help the Dalit ‘understand’ that this police station is not just for Rasulpura.

The Women’s Rights Commission claims that instead of protecting the women complainants under the special laws put in place to prevent oppression, the station-in-charge often ends up arresting those who come to file the case.

For example, Sualal Bhambhi from Rasulpura, along with his wife Geetadevi and daughter Renu, had come to file a case against Biram Gujjar for resorting to violence in an attempt to take away their cow forcibly. The police, however, arrested Sualal Bhambhi instead, saying that the true culprit would become apparent only after investigation.

When the Women’s Rights Committee and the Dalit Rights Centre intervened, he was let go. But while the police were willing to look into the case of a stolen cow, they were unwilling to register the case of physical violence against his wife and daughter.

Bhanvaribai and her associates, however, were let go soon after I reached the police station.

An unending struggle

The history of Dalit struggle in Rasulpura goes back a long time. It was only 10 years ago that Harikishen, a teacher, broke the age-old taboo that forbid Dalits to ride a horse to their wedding (as is common practice among Hindus in this region).

15 years ago, Chaggibai won a Panchayat seat without any reservation, defeating many contestants from the higher caste communities. However, when she won, higher caste men surrounded the school building in the village and Chaggibai had to be rescued by the police. Within six months, the Panchayat community removed her because they felt that a Dalit woman in the Panchayat lowered:the prestige of the village.

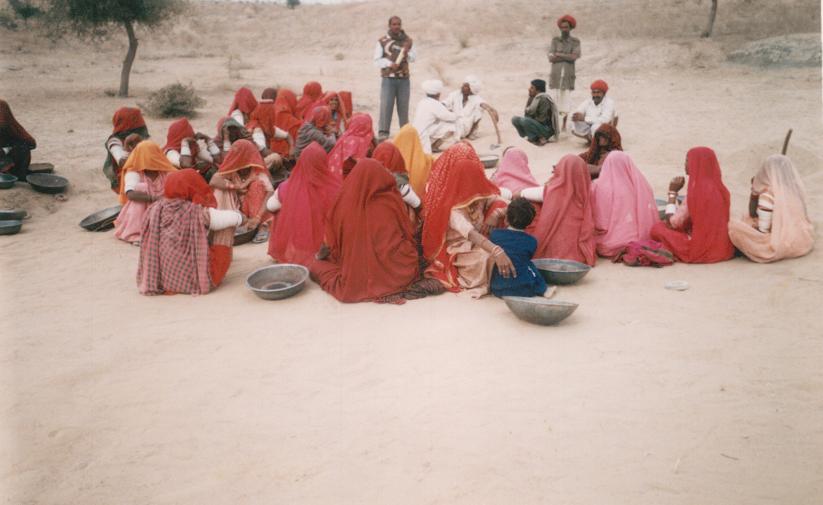

Dalit women at Rasulpura village in Ajmer, Rajasthan. Pic: Shirish Khare

Around the same time, the women of this village decided to speak out about their rights – they formed a “Women’s Rights Committee.” Women had to pay Rs 2 to join the group and 12 of them joined. They used the committee to talk about their daily problems and its solutions.

Bhanvaribai tells me that five years after the committee started functioning, opposition to the group began to rise as it also started to voice opinions on child marriage, and casteism. When Dalit women began to take exception to caste-based insults and abuses, upper caste people questioned these sudden objections – after all, this had been the norm for years. Now, though, this began to cause conflict.

Kalyanji, a Dalit villager, says that upper caste members of Rasulpura are interested in taking over 30 acres of land that belongs to Dalits as well as 4 acres of government land. 1 acre costs about Rs 100,000 at current valuations. Land is the primary source of income for these Dalit communities, but now they are being pushed out or forced to part with their holdings under threat of violence.

On 12 February 2013, one Mamchand Ravat along with some other men entered Dalit villager Shankarlal’s house, and beat him up. Despite the intervention of the Dalit Rights Center, a case was filed only after three months and it has been six months since that; nothing further has happened. Teja and Amba Gujjar have also been involved in other incidents where they have beaten up women. A report was filed only after the local SP intervened, but there has been no progress since.

In an interesting case of communal collaboration, the Muslim community in Rasulpura has been providing support to the upper-caste Gujjars – a result perhaps of political and social alliance. Two big Muslim traders have come out in support of the Gujjars - one even threatened major violence if a single Gujjar was arrested.

It is never an issue of how big or serious the case is. Whenever there are instances of oppression against Dalits, especially Dalit women, all agencies of society - the neighbourhood, the village Panchayat, the police and the local courts - assume an attitude that makes justice impossible. Negotiating the basic necessities of life in the face of such adversity is an everyday reality in a Dalit woman’s life.