I was walking to a book sale last month when I noticed a yellow hanging that said (I am quoting from memory; the exact wording might have been slightly different): "India, do you want to be as developed as China?", and then went on to offer some advice, which included "eradicate corruption" and "end dirty politics".

The failures of governance and development in India are poignant when we compare our superpower dreams with the (imagined) superpower reality of our northern neighbour. Still, we know too little about China to really understand why China has moved so far ahead. I don't know much about the actual conditions in China, and I suspect that most of the Indian political and bureaucratic class shares my ignorance. With the commonwealth games fiasco reminding us of the distance between Delhi and Beijing, the best we can do is to use the embarrassing comparison with Chinese power and efficiency to reflect on our own failures.

A good place to start our reflection is with the desire to end corruption and dirty politics. There is no shortage of corruption or politics in our country, but in my opinion, these are symptoms rather than causes of the malaise. The problem lies deeper.

To see why the problem lies deeper in the structure of Indian institutions, let us first note that these criticisms are specific to the urban middle classes. A rural dalit might consider politics to be the only ticket out of oppression, since neither economic nor social methods of advancement are readily available. Even if we take the urban middle class aspirations such as good governance and efficient delivery of public goods as universal aspirations, I still do not think that laziness, corruption and politics are the real problem.

The usual reasons

Most Indians work with their hands, as farmers, labourers and factory workers. When they have work, they work hard; they are idle only when work isn't there to be had. They might be unskilled and their work of low productivity, but they are certainly not lazy. If our education and health systems had been better, the vast majority of Indians would have more productive skills and a healthier body capable of using those skills. The failure is institutional, not individual.

Similarly, I am not so sure that corruption is responsible for poor governance. From published evidence, China seems as corrupt as India. Transparency International's global ranking of nations has China at #79 and India at #84, with only one country - Serbia - between the two. Perhaps the difference is between enabling corruption and disabling corruption, or, to put in layperson terms, the Chinese take bribes and get the job done while Indians take the money and run. In many countries, corruption is the price of doing business, but there is no reason why corrupt officials shouldn't deliver the goods.

While blaming individual politicians and babus for their corrupt ways, let us also examine the system that accepts mediocrity and even lets it thrive.

•

Politics in need of revival

•

The Dr Watson problem

•

The chancellors' vice

As far as politics goes, there are plenty of "advanced" countries where politics is divisive and bruising . Italy, the United States and Israel, for example. But politics doesn't have to get in the way of development. Despite the ruthlessness of Israeli politics, no major Israeli politician can afford to be seen as incapable of providing security and prosperity (which leads to an unending militarism, but that is another story). The problem of Indian politics is not that it exists, but rather that success doesn't seem to be connected to the ability to govern. It is the gap between competence and performance that poses the greatest threat to the Indian system, not corruption.

Tolerance of incompetence

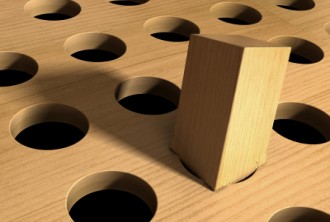

As I have argued in other essays in this newsmagazine, Indian science and Indian academia in general have also failed to deliver results. I don't think corruption and politics threaten the science establishment in the same way that might threaten the political system. Instead, what Indian politicians and bureaucrats share with their scientist, engineer and carpenter counterparts is their acceptance of mediocrity and lack of skill. The greatest moral failure of India institutions is the tolerance of incompetence, not criminality or corruption; the tolerance of incompetence in turn is a result of a low cultural value attached to the creation and sustenance of institutions (as opposed to increasing individual or family wealth, power and prestige). When we cannot make doorknobs that fit, how can we aspire to becoming a superpower?

Institution building is hard work; it requires a combination of vision, commitment and performance. Any institution involves a contract between those who belong to the institution and those who support it; without the support of the Indian people, the central government will cease to exist and without the support of the local populace, the neighbourhood market will cease to exist. The support can take the form of money or votes but that support must be earned continuously.

In a properly functioning institutional system, the institutional contract between the institution members and their supporters takes the form: you give me support (money, votes) and I will give you results. Hospitals earn their support by curing patients, universities by creating knowledge and politicians by governing wisely. Competence is the channel that sustains the flow of trust from supporters to institutions and back. If doctors don't cure will they not lose our trust? If teachers don't know their books, will they be respected? While blaming individual politicians and babus for their corrupt ways, let us also examine the system that accepts mediocrity and even lets it thrive.

Individuals will always vary in talent, ambition and honesty. We cannot and should not enforce uniformity at the individual level. However, institutions are not individuals; when we enter into a contract with an institution, either as an employee or as a customer, we are leaving the world of private taste and entering the world of public performance. It is the duty of the institution to adopt standards of performance in its employees and to justify the trust of its supporters. The moral foundations of an institutional contract lie in the acceptance of mutual responsibilities . including those of performance . in return for mutual rights, such as the right to work. Underlying the institutional contract is the idea of mutual cooperation, that it is better for all of us to accept certain demands on our time and skills in return for beneficial rewards.

What we are seeing in India is a case of contract failure . the contractor who bribes an official and then builds a leaky stadium is not just being corrupt. He is sustaining a collusive system that subverts rules regulating mutual cooperation between government institutions, market players and society as a whole. In the case of endemic contract failure everyone suffers, including the contractor, for once the public loses its trust in institutions, even businessmen will lose out on opportunities to make money. The moral status of institutions is central to continued development and prosperity.

Despite the caricature as an advocate of the 'invisible hand', Adam Smith knew that prosperity is based on trust. One can be a robber baron for only so

long; after a few decades of robbery, there isn't much left to loot.