The Public Distribution System (PDS) is often labelled as a leaky and costly system, while cash transfers are portrayed as the magic bullet to reduce corruption and government expenditure. The government is therefore impatient to implement cash transfers in place of food grains once the necessary requirements like digitisation of beneficiaries’ data along with linking of Aadhaar number with the bank account are in place.

While selecting the areas for implementing the pilot programme urban areas were given priority as banks are more accessible there. Hence Chandigarh, Puducherry and Dadar and Nagar Haveli were finalised. However, the pilot in Dadar and Nagar Haveli has not even taken off due to public protests over the fear of food insecurity.

There were large scale protests against cash transfers in Puducherry following an earlier attempt of the pilot in February and March 2015 as a result of which the pilot was stopped after eight weeks. However, since September 2015 cash transfers have resurfaced not just in Puducherry, but also in Chandigarh.

Although public protest and mobilisation of opposition parties against cash transfers happened in this round too, the transition from food to cash has been unfolding uninterruptedly. While Chandigarh has made a complete transition to cash transfers i.e. people do not receive any food grains, Puducherry has made a partial transition i.e. people receive both cash and food grains (of a lower quantity).

Chandigarh’s experience with cash transfers

A survey of this transition to cash from food grains in Chandigarh by the Centre for Equity Study (CES), reveals that many families have been hit hard and desperately want the old system of receiving ration from the fair price shops (FPS) to be brought back.

Urban poverty in the uber city- Invisible, but not non-existent in Sector-56, Chandigarh. Pic: Shikha Kansal

The survey was conducted with 200 households across five areas in Chandigarh from 21 to 27 December 2015. Based on the addresses given in the list of beneficiaries under the National Food Security Act (NFSA), available on the website of Chandigarh’s food department, households and localities were randomly selected. The shortlisted localities were Dhanas, Hallo Majra, Khuda Ali Sher, Sector-26 and Sector-56.

Astonishingly, the survey findings suggest that more than 40 percent of the households were not receiving the cash entitlement under the direct benefit transfer (DBT) model in spite of their names being on the list. Families have been checking the balance in their accounts, but have not received any of their cash entitlements.

Panna Devi travelled 7 km from her residence to Sector-7 on 4 December only to find out that she had not received her cash entitlement for any of the previous three months. She has a small family of four and they are entirely dependent on the daily wage earnings of her husband. In the absence of ration or the cash subsidy, she has resorted to purchasing ration on credit from the local kirana (grocery) shop. About 32 percent families have begun purchasing ration on credit since the distribution of wheat and rice through fair price shops (FPS), commonly known as depot, has stopped.

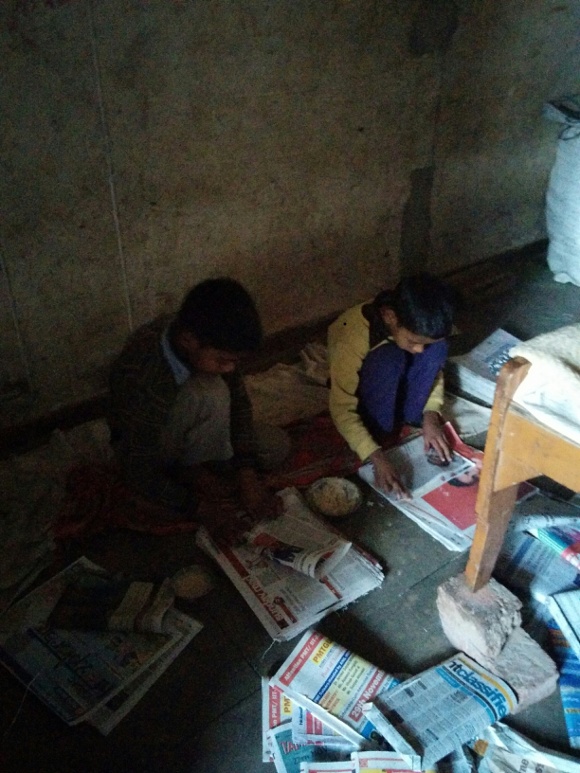

The impact of not getting ration or cash was more severe on large families. Razia Begum, a mother of eight children, had to stop sending her children to school so that they could help in making paper bags at home and earn enough to meet the family’s food requirements.

Children forced to work to make ends meet when denied their food entitlement. Pic: Shikha Kansal

Under the NFSA they used to get 30 kg of wheat and 20 kg of rice, while their father’s daily wage earnings were spent in buying other necessities like dals, vegetables and other items. However, since the launch of cash transfers Razia’s family has neither received ration nor cash. The family has been unable to stabilize their expenses and stop the children’s education as a way to increase the family’s income.

The Chandigarh administration implemented NFSA in 2014. Under NFSA every month each Priority family is entitled to 5 kg of food grains per person, while Antyodaya households receive 35 kg of foodgrains per household. Additionally, the Chandigarh administration provided 10 kg of wheat to all households that erstwhile belonged to the below poverty line or above poverty line households. However, in the new system only Priority and Antyodaya households are receiving cash which is equivalent of their entitlement under NFSA. A cash equivalent of the additional 10 kg is not being provided.

Making the matters worse, the Department of Food and Supplies in Chandigarh officially confirmed to the CES survey team that out of the 55917 families identified (i.e. Priority and Antyodaya combined) under the NFSA, only 42004 families are receiving cash transfers at present.

The remaining 13913, or 24.8 percent, eligible families have not received the due cash entitlement because their Aadhar or Unique Identification (UID) number is not linked with their bank account. In other words, the bank account of these households is not seeded with their UID numbers. When asked if these households have been informed about this, the official coldly said that the department has published public notice on this in the newspapers.

For these households, the due cash entitlement that is equivalent to the monthly subsidy given on foodgrains will be transferred only when the Public Finance Management System (PFMS) validates their UID and bank account numbers. However, this will not be done retrospectively. This effectively means that if a previously non-validated household is validated by the PFMS in the upcoming months, their entitlements for the lapsed months will not be given.

Based on the data from the field survey, so far, only 26 percent families have received their cash entitlement at least once since between September and December 2015. The timing of the transfers was also erratic. Those who received the cash on 14 September did not receive their October entitlement till 20 November. Many didn’t receive the September money till mid-October. In some cases, the money was received only in November or December.

Further, 31.5 percent of the total households were not aware whether they had received their entitlement, as they had not checked their bank balance in the past four months. This included people who are economically well-off (some in fact even met the exclusion criteria for identification of priority households and were therefore wrongly included), as well those who did not access bank as they were unfamiliar with the banking system; dependent on their husbands to operate their bank accounts; or those who would lose a day’s wage in going to the bank. Some hadn’t checked their accounts because their neighbours told them that the money hasn’t come and so they have decided to wait before making a trip to the bank which costs Rs. 30-40 on an average.

People’s preference

After experiencing the DBT system for more than three months, 71 percent of the surveyed families said that they prefer the depot (PDS) system over cash. The reasons given for preferring the ration system were price rise, better quality of rice in the depot than what they can afford from the market, greater proximity to the FPS than bank, ability to purchase ration in bulk among others.

Surprisingly, people chose ration over cash despite having many complaints with the functioning of the FPSs. These complaints included long queues, delay in delivery of food grains, poor quality of wheat, ill-mannered FPS dealers, black-marketing and others.

Women's unanimous vote for Ration in Dhanas, Chandigarh. Pic: Shikha Kansal

In fact, more than 44 percent families felt that the leakages and corruption in PDS can be plugged if the government is willing enough. Only 29.5 percent believed that DBT system alone can reduce corruption, while 24.5 percent were neutral in their opinion.

Nevertheless, in terms of food security nearly three-fourths of the households found PDS a better system than cash. Many women overwhelmingly said, “Ration main barkat hai, paise main nahi” (ration renders prosperity, not cash).

Some of those who were receiving cash even felt that the transition to cash has increased their food insecurity because the amount of cash given is not sufficient to purchase the same quality or quantity of food from the market.

At present only Rs. 94.50 per person per month is being given in place of 5 kg of foodgrains. Women, particularly, expressed their increased sense of anxiety with the grain containers in their homes, which were earlier filled with the entire month’s ration, being empty. It is evident that not only has the transition from food to cash been marred with implementation gaps, but it has also made people more food insecure in Chandigarh.

While some implementation gaps can be fixed, the usage of Aadhaar to deliver people’s legal entitlements under the NFSA is violation of the Supreme Court orders dated 11 August 2015. The apex court’s order clearly states that “production of an Aadhaar card will not be condition for obtaining any benefits otherwise due to a citizen”. Despite this the Chandigarh administration has made it a mandatory document and denied entitlements to nearly a quarter of existing beneficiaries under NFSA.

The NFSA is now being rolled out across the country. Initial reports from a number of states suggest that it has increased people’s access to food grains and is accompanied by an improvement in the functioning of the PDS. While leakages in the PDS, which is the main reason being given for a shift to cash transfers is a genuine concern, experience shows that this is declining and there are ways in which the PDS can be reformed.

These reforms can be expanded coverage, computerisation of databases, proper monitoring, door-step delivery of food grains and other ways as has been done in some states in the country. Bihar, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh have already exemplified how this can be done. On the other hand, the initial experience of cash transfers is showing huge implementation problems along with increasing people’s vulnerabilities.

Dismantling of the PDS has also made people more vulnerable to price fluctuations in the market. Before going ahead with this plan to replace the PDS with cash transfers, the central government needs to take note of people’s opinion, which is clearly in favour for foodgrains rather than cash.

NOTE: Personal details of people in this story were changed to ensure confidentiality.

References

Narayan, S. (2015). Why Cash Transfer’s First ‘Beneficiaries’ Want to Opt Out of the JAM. The Wire.

Dreze, J., Pudussery, J., & Khera, R. (2015). Food Security: Bihar on the move. Economic and Political Weekly, 50 (34).