: The western ghats region is not one that has any dearth of rainfall, and yet there many areas with considerable water scarcity. Kasaragod district in Kerala, for instance, enjoys an annual rainfall of 3500 mm -- this is 14 million litres (1.4 crore) of rainwater falling on an acre of land. Still, one block in Kasaragod is designated as a black zone. In this region, a traditional water extracting system called suranga - man-made caves for water -- has survived the test of time.

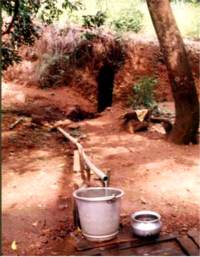

![]() Running water from the suranga (see opening on the slope) comes in handy

for drinking and washing vessels.

Running water from the suranga (see opening on the slope) comes in handy

for drinking and washing vessels.

Surangas tap groundwater by intercepting the water table in the area. The water is further carried through a downward slope on the floor of the cave, lowering towards the suranga's mouth. Water flows out without the help of a pump, and this is an advantage of surangas. To escape crab menace, sometimes pipes are used in the front portion of the suranga. The surangas in this region supply very clean 'running' water! Though most of them are used for drinking water, some irrigation is also done.

During the rainy season, water-flow is higher. In many cases, except where suranga water is directly picked up for drinking, water is collected in an earthen storage tank. From the tank, farmers open the sluices to irrigate their gardens (gravity) and also use sprinkler jets or drip.

Generally, a suranga is dug at the back of a hill. It's by intelligent guessing that villagers select the location. On occasions, they go wrong too. But generally, they don't use instruments like 'Y' forks or other water divining aids to guess the water source.

How do people decide to dig a suranga and not a well? Both structures tap underground water. Much depends on the topography in which one lives in. Surangas are natural selections in hilly terrain and sloppy areas. They are excavated horizontally either across a hillock or from under the depth of an existing well. People living downhill can dig a suranga and let gravity bring the water out. People living on hilltops cannot go in for a suranga because there is no hill portion or sloping land above their level.

![]() Dug out soil being transported out. At the far end is the mouth of

suranga where the water will flow out. This suranga, already 150 feet in length, is

yet to strike water. The light beam is sun-rays reflected from a mirror from outside.

Additionally, candle light is also used. The dead-end of the suranga where further digging

will go on is behind the spot from where the picture was taken.

Dug out soil being transported out. At the far end is the mouth of

suranga where the water will flow out. This suranga, already 150 feet in length, is

yet to strike water. The light beam is sun-rays reflected from a mirror from outside.

Additionally, candle light is also used. The dead-end of the suranga where further digging

will go on is behind the spot from where the picture was taken.

Cost is a factor too. Digging a new well usually involves higher costs due to the need for labour. Surangas on the other hand can be dug by just two people, like a father-son combination or two brothers during spare time or at night. If poor farmers or farm-labourers do not have access to hilly slopes above their house, they may dig a suranga a few feet below their house and carry water up.

The attractive colour of the suranga walls comes from the laterite soil. The walls have an ornamental texture. A pick-axe is the main tool used for digging surangas and it is the pick-axe marks that create the texture on the walls. The length of a suranga is measured in kolu. One kolu is 2.5 feet. There are surangas that stretch upto 150 kolu (375 feet).

Surangas are suitable only where there are hard laterite soils. This way they don't get filled or crumble. Also, they remain relatively insulated from higher temperatures. Even in the hot month of May, it feels like an air-conditioned chamber inside. The water is usually cold. In some surangas, the water source dries up in the summer months or dwindles.

Surangas are similar, but not identical to the qanats of Iran. Qanats tap underground water too, but are they are tunnels, open at both ends. Qanats connect a series of wells to supply the water. Surangas intercept ground water directly and do not rely on a well.

Unlike check-dams, surangas are not community structures. A family may have one or two or even six surangas.

![]() Irrigation tank fed by suranga water in Padre village, Kasargod.

Irrigation tank fed by suranga water in Padre village, Kasargod.

Padre village, which has around 900 houses, would have around 2000 such structures in use, at an average of 2 surangas per family. There is a wide variation in the numbers. About about 200 families have 4-6 surangas, while others have only one or two. There are very few families have none. My home, for instance, taps water through three surangas.

In Bayaru village, about 40 kms from Kasargod district headquarters, there may be far more surangas. By one 'guestimate', 40% of that village's irrigation requirement is met by surangas. On the whole, Kasaragod district may be having at least 6000-7000 surangas.

Though the art of suranga-digging is dying out, a handful of professional diggers are based in villages like Bayaru, Padre (Kasargod) and Manila (Dakshina Kannada district, Karnataka). In-depth scientific studies and documentation of this rural engineering skill has not been done so far.