Certain symbols seem to grip bureaucrats’ and politicians’ imagination when it comes to iconic edifices in a city. The classic example in Mumbai six years ago was a humongous Ferris wheel a la the London Eye: it was proposed at various sites along the seafront, much to the apprehension of local residents.

One of the main proponents was the former municipal standing committee chairman Ravindra Waikar who was smitten after a visit to London and wanted to replicate it in his city. He is now the state’s Planning Minister but in the dock – an appropriate metaphor for his earlier unsuccessful foray on the waterfront – for appropriating some land belonging to municipal parks.

The flavour of the moment appears to be Burj Khalifa in Dubai – the world’s tallest structure -- which the newly-appointed Mumbai Port Trust (MPT) Chair Sanjay Bhatia approvingly referred to at a May 23 conference on redeveloping the city’s port lands. The meet was called by Apli Mumbai, a citizens’ group which convened an earlier conference in the docklands in 2014 and submitted a slew of proposals. Like many such initiatives, the authorities have turned a deaf ear to them.

It doesn’t appear to have crossed Bhatia’s mind that this high-rise and others of its ilk are condemned by planners throughout the world as being indicative of the most wasteful and environmentally destructive form of development: an oasis of luxury in land reclaimed from the sea for this purpose in a desert country. As it is, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has about the world’s worst ecological footprint. We have only to recall the flak that Vijay Mallya received for his insensitive tweet from the highest-rise restaurant in the world about the breathtaking view, at a time when he hadn’t paid his employees for several months.

The rationale for going in for such luxury development would undoubtedly be to cross-subsidise other social amenities that have also been proposed for the 709 hectares that comprise this port land, making the MPT Mumbai’s biggest landlord.

This is three times the area of the land previously belonging to cotton mills, which was the focus of heated debate when its redevelopment came up in the 1990s. The MPT can redevelop as many as 287 hectares, while it asserts that the remaining 422 ha are required for the docks, roads, operational and residential areas. There is a 28-km eastern waterfront, which is protected from the southwest monsoon which batters the western seashore and is highly coveted by builders.

A similar cross-subsidy justification was used by the erstwhile Shiv Sena-led state coalition in the mid-1990s to buttress the controversial slum redevelopment programme: rehousing existing slum dwellers in return for building high-rises to pay for free housing.

Once any up market development like a Burj Khalifa comes into existence in the docklands, it inexorably sets in a chain reaction where market forces appropriate use of most of the land in question, with a token genuflection to social needs.

Even a previous committee appointed by the former MPT chair, Rani Jadhav, on the port land redevelopment, took a somewhat similar line. It recommended, along with a Ferris wheel, at least three marinas to dock luxury liners, a cruise terminal, several helipads, aquaria, water sports and floating restaurants.

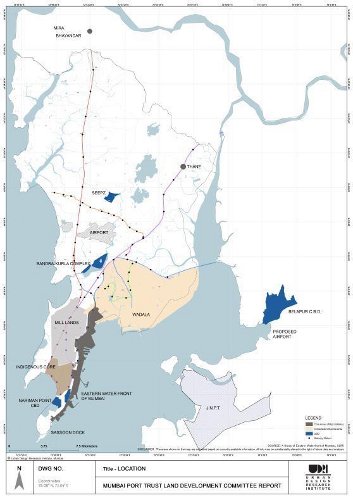

Mumbai port redevelopment plan as per the Rani Jadhav report. Map: Rani Jadhav report

Why this report has never seen the light of day is a mystery. It is of a piece with the report by the late Charles Correa on the redevelopment of mill land in the mid-1990s, which was similarly suppressed. If the Jadhav committee report is a public document about land belonging to the public, the authorities owe it to citizens to explain their rationale for keeping it out of sight.

Decision-makers have only to see what happened to London’s Docklands, which underwent a complete overhaul under Margaret Thatcher, doing away in toto with all planning intervention in favour of the free market. The Docklands are now the heart of the City – with a capital T, the world’s international finance centre (or was, till Brexit). But the dockworkers and old residents have been ousted in favour of high-rises where people commute to work; the area is a ghost town at night. This is gentrification of the worst kind. Exactly the same has happened with what used to be called “Girangaon” – Mumbai’s mill district: mills have given way to malls and office skyscrapers.

Bhatia spoke of his “aspirations”, including a ropeway in the docklands, but added that there were “constraints”. He would have to initiate consultations with stakeholders. That includes a dialogue with some 2,500 tenants who occupy 275 ha and bring in a revenue of Rs 150 crores a year – microscopically less than what would be raised if these were put on the market.

The properties include the iconic Taj Mahal Hotel near the Gateway of India. Even if the MPT doesn’t renew these leases, the tenants’ eviction is a cumbersome legal process. Existing land use norms would have be revisited, and only port-related functions would continue as commercial activity.

To complicate matters, there are also 35,000 pensioners and employees who have to be compensated, including where possible by rehousing them. The time-tested method would be to place the area under a Special Purpose Vehicle, which planners love because it frees these jurisdictions from social reservations and other impediments.

Union Road Transport and Shipping Minister Nitin Gadkari had recommended the formation of a Mumbai Port Lands Development Authority to take over these lands, given that the MPT doesn’t have the expertise to manage them. Bhatia referred to a Project Management & Implementation Consultant to step in for this purpose. However, the loss-making body will lose control over revenue from this area which – unnamed senior MPT officials say -- is “frightening for us”.

Under Bhatia’s “action plan”, leases won’t be renewed. The MPT will sell or lease very valuable plots in Ballard Estate – the former commercial centre – and Apollo Bunder (where the Taj is located). The Victoria and Prince’s Dock could be redeveloped as a marina and other “high level” development, according to Simon Arrol, a top British consultant on yacht marinas, who spoke at the conference.

He was involved in redeveloping St Katharine’s Dock in London (interestingly, some of those docks were named after its “jewel in the crown”, like the erstwhile East India Docks, while Mumbai has some named after British royalty). He believed that the Prince’s and Victoria Dock in Mumbai, which was filled in to convert it into a container terminal but then shelved, could be excavated to serve as a marina, as could the Indira Dock.

Others referred as precedents to Battery Park in Manhattan’s waterfront, where 92 acres have been converted into an open area and ferry terminal as part of New York City’s Master Plan. Another location is Le Vieux Port in Montreal, which has undergone a similar transformation as has the iconic Embarcadero in San Diego, California.

The needs of the public have, expectedly, taken second place to the high-end uses in Mumbai. These include open space in a city where each Mumbaikar only has 1.2 square metres to her or his name. There could be waterfront amenities like promenades, cycling tracks and water sports.

Public transport has found a mention in both Jadhav’s and Apli Mumbai’s reports: rail/Metro, road and marine, the latter providing easy access to the mainland across the harbour. But here again, even in “citizens’ aspirations”, creep in seaside developments like hotels and a convention centre.

If an international finance centre is a constant aspiration among decision-makers in Mumbai, it is simply because it already attracts an FSI of 4 and that is certain to go up if and when the second version of the city’s 20-year Development Plan comes into effect later this year.

While Gadkari and Bhatia have promised complete transparency in the plans to redevelop this last remaining opportunity to provide public amenities in the city, they could surely prevail upon the powers-that-be to release the Jadhav report and expose it to public scrutiny. Any failure to do so will only strengthen the impression that there is more to this area than meets the (Mumbai!) eye.

The experience of London’s Docklands should serve to warn against gentrification and the conversion of derelict port lands should use these huge tracts of land for a genuinely public purpose. Among the first needs is to rehouse the port workers who may have lost their livelihood or are in danger of doing so, particularly with the modern Jawaharlal Nehru Port across the harbour which can receive and send imports and exports to other parts of the country without congesting Greater Mumbai.

The MPT can take a leaf from the National Textile Corporation, which has just provided homes for 16,500 mill workers’ families for just Rs 9.6 lakhs each without any subsidy, given that the land is free.

The port lands, which extend from Colaba in south Mumbai to Sewri midway through the island city, should primarily benefit citizens at large, who now have no spaces for recreation. As this derelict tract extends northwards, it lies cheek by jowl with heavily congested areas, with no open space.

Two of the few remaining beaches, which see literally thousands of visitors daily, Chowpatty and Juhu, are in imminent danger of being built over by a Rs 11,000-crore coast road throughout the length of the western seafront.