Documentary films have been recording factual contemporary history for a long time, much to the discomfiture of the powers-that-be. But feature films based on contemporary happenings that touch upon sensitive issues - like terrorism, police torture or communal riots - are more or less, a comparatively recent development. And about time too, for they have also offered Indian cinema a boost from its usual masala, by making movies that are cerebral, reflective emotional and informative. These movies make you think, they are moving, and they tell you things you would never have known from newspapers and news channels. Firaaq is the most recent of this lot.

The city, in its modern labyrinthine form, offers the ideal environment for a film that combines several genres in one. It can tell not one, but several stories of different people who may or may not meet at any point, yet, are affected by the city they live in, albeit in different ways. Can they cope with the stress and the strain the city places them under? Do they cope? How and in what manner? These questions are raised, and a few answered as well, in Nishikant Kamath's Mumbai Meri Jaan.

•

Documentaries explode myths

•

Still suffering, 5 years after

Firaaq goes a few steps further than the older film. It exposes the underbelly of a city on the verge of moral and physical collapse where, Hindu or Muslim, some minds and many bodies are damaged forever. A few look around to take stock of their bearings in this changed scenario of hate, danger and uncertainty to move ahead, come what may.

"Firaaq is a film that reinforces the meaning of human relationships. It talks about how communal disturbances in society affect relationships on an interpersonal level. It traces the emotional journeys of ordinary people. I chose this subject because I thought it would click with the urban audience. Every time I think about this carnage, I feel helpless so this is my way of portraying my thoughts. This is the first time I really got to express my thoughts in the way I wanted," says Nandita Das about her film.

A bunch of young men, victims of the riots following the carnage, seeks bloody revenge in its helpless anger and hate. A modern day Hindu-Muslim couple struggles between the instinct to hide the name and identity of the Muslim husband and the desire to assert it. A little boy desperately searches for his missing father, having lost the rest of his family in the riots. A saintly musician clings on to his idealism, despite all-consuming violence in the city, until an incident leaves him devastated and he decides to call off his daily recitals to a regular audience that no longer comes to listen.

While the characters are distanced in their communal identities, their lifestyle, age, experience and vocation, at times interconnected and at times distanced, they are bound by the pain these ordinary people are going through, constantly egged on by the fear of an uncertain future where tomorrow may never happen. Firaaq is an insightful and incisive approach towards the impact of the Gujarat carnage on members from either community whose lives change forever. Through a few characters belonging to both communities, Nandita paints a powerful portrait of the identity problems of this victimised lot.

Separation and Quest

Firaaq is an Urdu word that means both separation and quest. Where is the separation in the film? It is the separation of human relationships in the aftermath of violence, not just beyond the four walls in a city under State siege, but also within the home. Aarti, a middle-aged housewife, is a lifelong victim of imprisonment at home with a husband who slaps her and insults her ever other minute. When she tries to take a little Muslim boy under her wing, hiding his communal identity from her husband, a staunch Hindu-Gujarati, he retaliates, the boy wanders away and Aarti, in an impulsive moment, walks out of her home.

Shahana Goswami as Munira in Firaaq.

The separation is also from loyalty between two best friends, one Hindu and the other Muslim, put to test where Munira begins to suspect her close friend who is actually trying to help her in her hour of need. Sameer vacillates between hiding his second name and revealing it lest it give away his Muslim identity. "Thank God your parents named you Sameer," says his Hindu wife, unwittingly hurting him deeply with the suggestion that perhaps, she regrets her choice of a Muslim husband. A man, who spies a young Muslim hiding under his balcony, drops a slab on the younger man, killing him instantly. Who is the perpetrator of this violence and who is the victim? After a point, the lines between the victimiser and the victim get blurred. From the physical separation between a little boy and the rest of his family, it reaches out to the separation of values from humans who till then, had held on to them closely.

The quest is for these people to rediscover themselves within turbulent times where peace is a Utopian ideal that no longer exists. Sameer realises that there is no running away from his roots or from his name; they make him what he is. The Muslim saint stops performing and the Hindu housewife walks away from her oppressive environment not knowing whether the world out there is better or worse than the one she lived in. Munira learns to cope with her friend's desperate attempts to hide her Muslim identity. It sort of quells her fears and also cushions the pain of coming back to a ransacked home.

"... Making Firaaq gave me the opportunity to express my concerns and beliefs," says Das. "It has also been a cathartic experience. It has pushed my boundaries and helped me grow both professionally and personally. I chose an ensemble structure because in mass violence there are no individual heroes or villains. When thousands have suffered, the suffering of only one person cannot be glorified. I wanted to explore the conflicting and complex emotions of fear, anxiety, prejudice and ambivalence in human relationships during times of crisis. The challenges for me lay in making a rooted and contextual film and yet garner a universal audience. I wanted to provide the necessary realism and the universality of emotions that would make people across cultures relate to it."

The film is generously sprinkled with touching moments captured by an almost caressing camera that takes its time to drill in the shocks, at the same time intercutting with scenes of arson in the backdrop with the dynamic pace needed to hold the gaining momentum of multiple narratives and characters. Aarti is haunted by deep guilt for not having opened the door to a Muslim woman crying out for help during the carnage. Flashes of a screaming woman banging on her windowpane keep coming back, and as a form of retribution, she keeps branding herself with a hot ladle while cooking. There is a montage of shots where the camera closes in on the bewildered expression on her face, as she looks out of the auto rickshaw at a city she cannot recognize anymore, or, cloistered and imprisoned in her home, she may never have set eyes on for a long time.

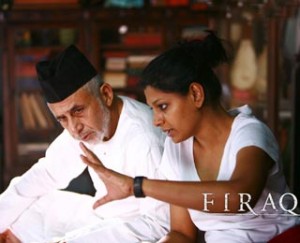

The acting cast is a happy mix of veterans like Naseeruddin Shah (pictured with the director below), as well as talented contemporaries and wonderful newcomers who have realised the trust Das placed in them.

•

Documentaries explode myths

•

Still suffering, 5 years after

The acting cast is a happy mix of veterans like Naseeruddin Shah, Paresh Rawal and Dipti Naval, talented contemporaries like Raghubir Yadav, Sanjay Suri and Tisca Chopra and wonderful newcomers like Shahana Goswami, Nowaz, and the little Mohammed Samad who have realised the trust Das placed in them. Co-scripted by Nandita herself with Suchi Kothari, the film stands enriched with its documentary-style cinematography by Ravi K. Chandran, razor-sharp editing by Sreekar Prasad, imaginative sound design by Manas Choudhury and a fitting music track jointly conceived by Rajat Dholakia and Piyush Kanojia. Firaaq makes a cogent, consistent and incisive analysis of people's minds when they are placed in a situation of catharsis they are in no way responsible for.

Firaaq is like a celluloid anthology that will carve a niche in the minds of the audience for capturing and freezing in time, moving images of the anger and anguish of personal responses to the Gujarat catastrophe. A recurring motif through Firaaq is the uncertainty that dogs the Muslim identity. It is not a happy metaphor, but one cannot escape its reality. The final close-up of the orphaned little Muslim boy's face who looks into the camera with the innocence of a child, not aware that his parents have died in the carnage, and is searching for his father who promised to pick him up makes you feel, in some way responsible for participating in this collective pain and torture of fellow-humans vicariously, as a member of a discerning but casual audience watching a film recording their suffering.