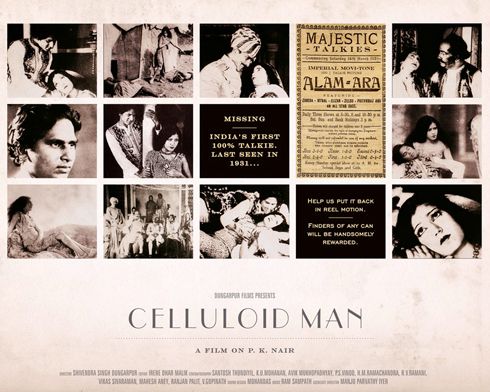

Celluloid Man is a film that is a tribute to Indian cinema in its 100th year and a celebration of the man who made it possible for us to know about these hundred years through his life dedicated to archiving the history of Indian cinema. This man is P.K. Nair, founder-director of National Film Archive of India (NFAI) in Pune. We would never have heard the name of Dadasaheb Phalke and his first film Raja Harishchandra had it not been for Nair.

Raja Harishchandra was released on 3 May, 1913 heralding the unveiling of Indian cinema. On 3 May, 2013, the Indian audience was witness to Celluloid Man, a 64-minute-long documentary that reveals layer by layer, the magic of cinema seen through the eyes of the man who re-created that history for posterity P.K. Nair.

There is a brief prologue. It shows a rectangle of light shot in Black-and-White leading an old, wooden staircase to the upper floor of the NFAI. The camera zeroes in on this rectangle as the shadow of a figure with a walking stick steps in slowly, the soundtrack filled with the sound of his walking stick. The shadow becomes a man and it is none other than P.K. Nair himself.

He clambers up the staircase, ever so slowly, to reach the narrow alleys between shelves of film reels, rattling off the titles and chosen reel number of films like Light of Asia, Kalia Mardan, Our Daily Bread, Blue Angel, Sant Tukaram, Hunterwalli, Queen Christina and PC Barua’s Devdas. The camera cuts between B&W and colour to merge the past with the present because that is what P.K. Nair is all about. Noted filmmaker Krysztof Zanussi says that for him, Mr. Nair is a symbol of the memory of cinema while late Sri Lankan filmmaker Lester James Peries says that Nair is not only an archivist but also a historian. He is the custodian of Indian cinema, because he has preserved the memory of Indian cinema as a form of art.

Pic: Shivendra Singh Dungarpur

One can hear that dialogue “Dada, I want to live” from Ritwik Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara as the camera pans across unending spools of celluloid and rusted film reels scattered across the grounds of the Archive. When Nair enters the room where he spent 20 of the best years of his life, we see empty shelves across the room apparently out of use after he retired.

•

A delightful celluloid recreation

•

Setting the stage on fire

Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, an FTII alumnus who was fascinated by this man’s commitment to retrieve and restore forgotten films, damaged films, destroyed films for posterity, suddenly felt this trigger to make a documentary on Nair who was living in Pune in retirement but was not permitted to enter the complex of the NFAI for reasons that are unexplained. It took Singh 11 trips to the NFAI to convince the powers-that-be that it was necessary to shoot within the complex and also for Nair to be present.

Shot entirely on film with eleven DOPs, Celluloid Man is a brilliant film that overlaps several genres history, biography, sociology and even politics. In a very understated manner, the film points out how the very man who made this history possible can be summarily rejected by the institution he built up from zero to what it stood to become. Brick by small brick - or rather, one film can by another film can - patiently yet determined, Nair built the National Film Archive of India in a country where few beyond films even know what archiving of cinema means.

It all began when Dungarpur decided to visit Mr. Nair who was living a retired life in Pune. He arrived to find that the Archive had been orphaned: rusting cans lying in the grass, thick cobwebs hanging from the shelves in the vaults and Mr. Nair’s old office turned into a junkyard. Mr. Nair had devoted his life to collecting and saving these films and Dungarpur was determined that his legacy should not be forgotten. And so the journey began.

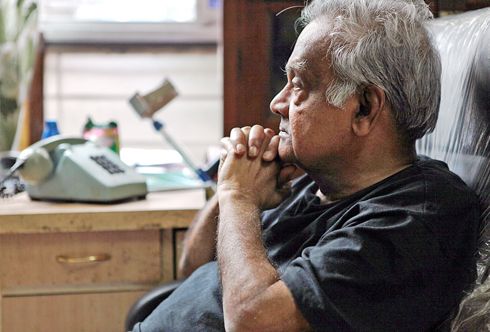

A still from the documentary, showing film archivist and historian P. K. Nair

Celluloid Man runs along three different levels which merge and blend as the film unfolds several stories. On the one hand, it concentrates on the life of a small boy whose love for cinema created for posterity a cinema archivist and historian, who resurrected the 100-year-old history of Indian cinema almost single-handedly for over 20 years. On the other, it unfolds the history of Indian cinema itself through the eyes of Nair who knows exactly on which reel of which film a particular scene or song sequence or dance exists and can pull that reel out to show it to you. No one has heard about an archivist with this phenomenally photographic and descriptive memory.

The third layer is tragic. It reveals the underbelly of the NFAI and its status quo as it exists in the present. The camera pans across film reels lying uncared for, neglected and turned almost to waste on the grounds of the NFAI on beds of dry leaves. We see loose spools of priceless celluloid either hanging here and there or lying in a heap, lost to time and history. There is no dialogue and no voice-over in these scenes, silence sometimes dotted with the music track of old films. The visuals do the talking.

Director Shivendra Singh Dungarpur.

“I remembered Mr. Nair as a shadowy figure in the darkened theatre, scribbling industriously in a notebook by the light of a tiny torch winding and unwinding reels of film, shouting instructions to the projectionist and always, always watching films. We were all a little in awe of him and had to muster up the courage to climb the creaking wooden stairs to his office to request to watch a particular film”, says Dungarpur who is happy that Celluloid Man won two National Awards this year. The film has already journeyed through 24 prestigious international film festivals including the 50th New York Film Festival, the 39th Telluride Film Festival, 49th International Film Festival of Rotterdam and the 37th Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Dungarpur began his career as an assistant director to his mentor, writer-lyricist and director, Gulzar. Gulzar suggested he enroll himself at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune to study film direction and scriptwriting. After graduating from FTII, Shivendra launched himself as a producer-director in 2001 under the banner “Dungarpur Films”. “I was always interested in preservation something I learnt from my father. I had read an interview with Martin Scorsese about the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, Italy where they screened restored films. I was so fascinated that I decided to attend the festival. I think the seeds of restoring and preserving concretely as my life’s mission were sowed with this decision. It worked like a trigger,” he says.

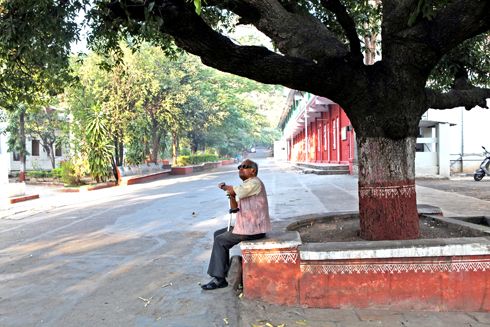

P.K. Nair under the Wisdom Tree. Pic: Shivendra Singh Dungarpur

Celluloid Man moves backwards and forward in time where Nair narrates how his love for cinema since he was a boy began with collecting and storing ticket stubs of films he had watched in a tent cinema. Though his father was strongly against his ambition, Nair was firm. He became an archivist though he wanted to become a filmmaker. His younger brother Ramana Kutty was the only one who encouraged him. About Nair’s first film, he says, “when I was about seven or eight, I sat on a floor with shiny white sand to watch a film made by K. Subramanian who made mythologicals. We had tent cinemas at that time and films that left a deep impression on me are Vigilante’s Return, Cecil De Mille’s Unconquered, Blue Earrings and The Lost Weekend.”

Nair recalls how when he went in search of prints of India’s first talkie Alam Ara to Ardeshir Irani’s home, the old man was still alive and his son Shapurji Irani was by his side. “Shapurji looked under the cot in the room, pulled out three reels of the film and handed them to me. As we were clambering down the stairs, he confessed that he had sold the rest of the film’s reels and other films for the silver that could be obtained from the nitrate based films. At that time, the selling price of the reels was Rs.100/kg for 35mm film,” says Nair. He considers Henri Langlois, a master archivist of cinema of the Cinematheque in Paris, his mentor whom he met personally when he went to Paris.

The title and credits of the film are designed to look as if written on a scratched piece of B&W celluloid film, like an archival film strip. The graphics follow the style and pattern of fonts used in very old Indian films. “For me, cinema began as a wonder and a magic when I was a boy. Later, it became a kind of obsession and then a passion. Now, looking back, it has become a part of me and my life. I understood the world and the people better through cinema. Cinema opened my view of life itself because cinema is Life,” says Nair, as if to himself, softly, in his low-key manner.

Celluloid Man is an ideal blend of form, technique and content. It is shot against a live backdrop of old film clips, with famous old songs, or dialogue from old films on the soundtrack sometimes punctured by the sound of a live projector, interspersed with comments from great personalities of Indian cinema from Mrinal Sen to Gulzar to Shyam Benegal and Girish Kasaravalli extending to capture some famous FTII alumni. The cinematography is low key, alternating between monochrome and colour, never brightened with primary colours as it catches Nair in a long shot, sitting alone under the Wisdom Tree or zeroing in on his hands as he ties a knot at different points on a film reel.