In Indian cities, the use of land outside the demarcations of the Master Plan is a common feature. Settlements, markets, playgrounds are created, grow and thrive over time. These do not follow planning visions, zoning regulations or development control regulations. They develop organically as a result of people's needs. This is true for both greenfield, planned cities as well as older cities with diverse planning histories. Master plan revisions that take place once in two or three decades attempt to create order. These, however, often create chaos in people's lives who occupy, live, work and use these spaces. Forced eviction of neighbourhoods and livelihood areas for public infrastructure projects is an obvious example of this.

Despite its limitations, formal planning can be strengthened by engaging with and learning from efforts that engage with organic planning that exists in cities. This article traces learnings from practice-based planning research and city-wide campaigns that YUVA (Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action, an NGO that works on a range of urban development initiatives for the urban poor) and partner organisations have been involved in. These efforts are localised, and showcase important ways in which planning can be more relevant to cities and its people.

Researching plans, 'slums' and people

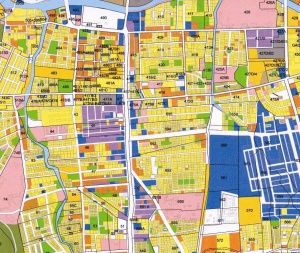

Research on how Master Plans engage with slums in Ranchi, Bhubaneswar, Indore and Guwahati show that despite the inherent diversity of these cities, there are overwhelming similarities - the homogenisation of diverse settlements of the urban poor, overriding local laws on tenure; poor baseline data of slums that informs the final plan; and a reliance on central schemes with associated and conditional funding that often override the Master Plan.

The term 'slum' homogenises varied settlements of the working poor that occupy a very small portion of the city's land but house a vast majority. Settlements are labelled 'slums' irrespective of their tenure, property rights, services, and history. For example, in Ranchi and Bhubaneswar villages that come into the boundaries of the Municipal Corporation are marked as slums, unseeing local tenancy laws and land ownership of residents. In Indore and Ranchi, select settlements that have secure land titles and invested in basic services are also classified as slums.

While revising the plan, the number of 'slums' used as the basis for planning is often not comprehensive. The number of slums differ in surveys. The Master Plan uses a survey that the planning authority deems fit while compiling the Existing Land Use (ELU). Hence, while planning itself there are a number of existing settlements left out of the plan. For example, the Guwahati Comprehensive Master Plan 2025, recognises 26 slum pockets based on a 2001 municipal survey while government surveys in 1997 found 40 slums and in 2009 found 90 slums. The Indore Development Plan 2021 report notes that there are 637 slums, while only 488 are mapped in the report.

Thereafter, at each step there are differences - the classification of slums in the Existing Land Use, Proposed Land Use and the Notified Land Use does not remain constant. Select 'slums' are recognised as residential/informal residential or variations of this in the ELU. By the time the notified land use plan is published they are either categorised as residential or various non-residential land use reservations such as agriculture, water bodies, transport, public utilities etc are superimposed on them. There are limitations to both these reservations. Broad 'residential' land use reservations unsee development needs of select settlements. Other hand, superimposed 'non-residential' land use reservations are a constant threat to the settlement's existence.

Illustration : Farzana Cooper

Illustration : Farzana Cooper

The trend of centrally-sponsored schemes overriding the Master Plan is seen in all cities. Current schemes such as the Pradhan Mantri Aawas Yojana, Swacch Bharat Mission and Smart Cities Mission are superimposed on the Master Plan, and while they sometimes support plan implementation financially, they also bring with it their own planning visions that threaten the existence of existing settlements of the working poor.

As pointed out by several scholars, a planning process that does not recognise living and working spaces of the working poor often end up reinforcing 'illegalities' and 'informalities' within a city. These studies illustrate the need for a rigorous, granular approach to understand, recognise and secure diverse forms of housing in cities. There should be emphasis on ground-level research conducted prior to finalisation of the ELU and assessment of planning needs of settlements prior to finalisation of the plan. This is crucial given that planning actions with regard to housing can deepen or alleviate not just housing inequalities of residents but the socio-economic inequalities in the city.

Building capacities: Understanding planning and its everyday impact

Along with research, simultaneous planning education is crucial to ensure people are able to understand and negotiate policy decisions. YUVA and the Indian Institute of Human Settlements studied how successive Master Plans in Indore have understood and provisioned for 'slums' or people-built housing in the light of the city's poor being rapidly displaced by multiple development projects. Through a series of capacity-building sessions, residents were trained to think spatially, understand the Master Plan and infrastructure plans in their city, and make decisions on housing choices based on visits to different types of housing.

Research on plans when coupled with planning education helps residents understand how planning impacts them, make informed decisions and allows them to negotiate with authorities for alternatives that respond to their needs.

People's campaigns on urban plans

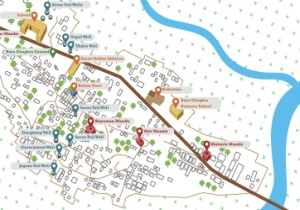

People-led campaigns have been powerful mediums to challenge existing ways of planning. YUVA has been part of two civil society campaigns to ensure greater inclusion in urban plans - Hamara Sheher Mumbai Abhiyaan (organised around the Mumbai Development Plan 2034 revision) and the Mein Bhi Dilli Abhiyaan (organised around the Delhi Master Plan 2041 revision). These campaigns have at the core of organising, the belief that citizens must participate in envisioning a city.

Through participation in these campaigns, people collectivise around their concerns about local spaces. This is especially important for communities for whom a collective is able to give them strength to claim what is rightfully their share in the city, when individuals cannot. Take for example, the Kolis - the fishing community in Mumbai who negotiated that their settlements, fish markets, livelihood areas should be reserved in the city's development plan, or the street vendors who negotiated for vending zones to be marked in the Master Plan in Delhi. Such organising was also seen by residents of urban villages, slums, waste pickers, women, youth, the differently abled etc. These are just few of the many groups in who were actively involved in the negotiating for space within plans.

While the window period for 'suggestions and objections' to the draft plan remains the only legally mandated space for participation in the planning process, these campaigns have been instrumental in ensuring wider participation of marginalised groups through formal consultations with planning authorities and actual negotiations for land use reservations in the Master Plan.

Making planning relevant to cities and its residents

A number of ways in which planning can be more responsive within the legal framework within which it operates have been identified based on such practice research and past experiences. Firstly, the organic plans' of citizens must be acknowledged by formal plans. The reasons behind the places and spaces they create must be understood. These are not aberrations, but responses to real needs - with or without the recognition by authorities. For plans to be responsive, there must be integration of what is organically planned through people's participation with the formal planning process, and local area plans must be encouraged.

|

Secondly, planning must be linked with governance. Through governance, participatory processes can be institutionalised; the plan can be implemented, financed and operationalised. Take for example, the case of homeless shelters in Mumbai. These had never been part of Mumbai's Development Plans and therefore there was no land-use classification for them. Between 2013 and 2016, the Hamara Shehar Mumbai Abhiyaan successfully advocated for homeless shelters as a land-use reservation. As of 2021, some of these shelters have been constructed or made available.

Even in such cases, there are often further difficulties. The operationalisation of these shelters is fraught with governance hassles. It took five years to ensure land-use reservation in the plan, and more than five years to ensure plan implementation via multiple other departments and layers of the Municipal Corporation and State Government. This is the case of not just homeless shelters but many social amenities that were provided land use reservations in the Mumbai Development Plan 2034.

Third, planning must acknowledge its social obligation. Planning should include, not exclude. To do this, plans must be based on values of justice. This will ensure inequality that is characteristic of Indian cities can be tackled to some extent by the planning process. Though this is a challenge, as the technical is confronted by socio-political reality; through sustained investment in planning through rigorous research, public education and enabling participation, this is possible.