Rohit Vemula’s suicide reveals, nearly 70 years after India declared itself to be “a sovereign, democratic republic”, the ugly underbelly of what the leaders take pride in by labelling it “India Shining”.

Though Vemula has categorically stated in his suicide note that he did not hold anyone responsible for his death, the echoes of reality are deafening on the one hand and shameful to confront on the other.

In June last year, two brothers from Pratapgarh, Uttar Pradesh, Brijesh (19) and Raju Saroj (19) cracked the IIT Entrance exams. The boys were ranked among the top 500 and when they came home from the felicitation function by the Chief Minister, they found that their house was pelted with stones. Their only fault is that they were Dalits. The Saroj brothers are sons of a Pratapgarh-based Dalit daily wage labourer. The same month, in a shocking incident, a minor Dalit girl was allegedly beaten up by higher caste women in Ganeshpura village in Chattarpur, MP, after the victim's shadow fell on a muscleman belonging to their family, police said.

Last May, hundreds of Dalits from Nagaur district's Dangawas in Ajmer near Jaipur and surrounding villages fled for their lives after the region's dominant upper caste, the Jats, mowed down three Dalits under tractors, and grievously wounded a dozen others following the flaring up of a decades' old land dispute. The Jat violence followed firing by Dalits in which one dominant caste member was killed.

Profiling Dalits in Hindi Cinema

In this ambiance of hate politics traced back to caste ism and its ancient dictates, Indian cinema dealing with the Dalits and their marginalization should not come as a surprise. The question however, arises on whether the films are created to cater to the box office value of the film, or whether it aims to reflect a true reflection of marginalization, oppression and torture.

Indian cinema is majorly dependent on its positive reception by the mass audience. Thus, it is natural for social scientists, film scholars and critics to question the intentions of Indian filmmakers. A glimpse into the history of Dalits in Hindi cinema will throw up some significant answers.

The first Hindi film based on the delicate theme of untouchability that comes to mind is Achhut Kannya (1936). Devika Rani and Ashok Kumar portrayed the two leads in the film. The storyline goes as follows: Caste prejudice and class barriers prevent marriage between Kasturi, a Harijan (Dalit) girl, and Pratap, a Brahmin youth – both childhood friends and in love. Soon, Kasturi is forced into a loveless alliance with one of her own caste. A chance encounter at the village fair brings the two lovers together. Kasturi’s husband, inflamed by jealousy and suspicion, attacks Pratap at the railway level crossing, where he is gatekeeper. While the two men are engaged in a fierce fight unmindful of a fast approaching train, Kasturi, in an attempt to save them, is run over and dies.

Before this, only two other films had touched upon the caste problem is any significant way – Nitin Bose’s Chandidas (1934) and V. Shantaram’s Dharmatma (1935).

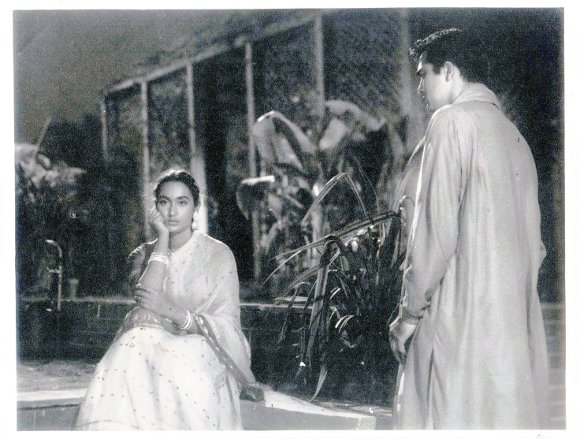

Nutan and Sunil Dutt in Sujatha (1959). Pic: Shoma Chatterji

Till this day, Sujata (1959) enjoys the status of a classic both at national and international retrospectives of Bimal Roy’s films and of Indian films. Its mechanisms of pleasure, blend of realism and idealism, and the humanitarian vision that it embodies denote a powerful, albeit fading currently in the symbolic universe of the 1950s. In and through Sujata, many of the oppositions that sustain between poverty and wealth, renunciation and worldliness, dharma and adharma, desire and law, the Brahmin and the Dalit – are worked out in terms of the family-as-nation/nation-as-family ideal.

Sujata is born into a Dalit family whose parents die in a cholera epidemic. She is brought up by a Brahmin overseer and his wife but she learns much later that she is adopted and belongs to the Dalit community. When she realises that something is wrong for her mother to repeatedly introduce her with, ‘she is like my daughter’, she creates a shell of self-imposed silence as expression of her feelings of betrayal by her foster-mother and also as her voice of rebellion.

Shyam Benegal’s Ankur (1974) and Nishant (1975) dealt with the oppression by the high castes. The trauma of a Dalit woman is reflected by the character of Lakshmi, portrayed effectively by Shabana Azmi in Ankur. The film provides a deeper insight into the ugliness of Indian caste system, particularly visible in the rural areas.

Manthan (1976) also portrayed the caste divide in the rural pockets of the country. All three films, without glamorizing or celebrating the casteist issue, focused mainly on how caste plays havoc with the lives of the low-caste who are also crippled by poverty and illiteracy. These films bring Benegal’s interest in power relations to the fore. The four-cornered struggle — among the untouchables, the traditional middle-class, the rising rural capitalists and the new cooperatives led by middle-class agents of change — all this is traced with a political consciousness which is evident in later films like Aarohan (1982) and Mandi (1983).

In Govind Nihalani’s Aakrosh (1980), Lahanya Bhiku a low-caste, poor and illiterate tribal, is accused of having murdered his wife Nagi. The woman had been gang-raped and murdered by the bigwigs of the village. Lahanya refuses to speak, even to his empathetic lawyer, who has risen from a poor background. While on death row, he is brought to perform the last rites of his dead father, his hands and feet shackled. As he circles the burning pyre, he lets out a final cry of anguish (Aakrosh) and slays his young sister, lest she befall the fate his wife did. This silence stands on its own.

Still from Damul (1985). Pic: Shoma Chatterji

Prakash Jha’s Damul (1985) is one of the boldest films that seamlessly explored the casteist and capitalist politics in some pockets of rural India like Bihar. The onslaughts on the oppressed come like a whiplash. An entire Dalit basti is held to ransom; the basti is gheraoed to stop the residents from casting their votes, subjecting them to the mandatory repayment of debts they had never taken, forcing them to steal cattle for the landlord who leaves them to die if and when caught, but not at his doorstep. The final blow comes when Sanjeevana, an innocent Harijan from the Dalit basti is sentenced to be hanged to death because he turned wise to the landlord’s wicket ways. Many years later, the same Jha made Aarakshan (2011). The film purported to be a socio-political drama based on the controversies revolving around caste-based reservations in Indian government jobs and in educational institutions.

Swati Mehta in Exploring caste in Hindi cinema (Meri News, April 04, 2009) points out how “..the majority of the stakes in the film industry is held by higher castes, their films portray a very elitist image and way of life. The culture and traditions shown in the films, for instance are very brahmanical. Or the concept of class has taken over caste in popular cinema. For instance, in Karan Johar’s films or in films made by Yash Chopra, one comes across titles like Raichand, Mehra, Melhotra etc, mainly high caste Punjabis who are rich businessmen. Their marriage ceremony is based on the Brahminical tradition with the priest given supreme importance. Lavish weddings and related ceremonies are another feature, which reflects the feudal nature of the Indian society. The rich and flamboyance can be attributed to the same.”

But there are been attempts to pay lip service to the caste schism in lavishly-mounted, high-budget and big-star films in recent times where the casteist issue is used as an agency to hit the bull’s eye at the box office, to get tax exemption for tackling a socially relevant issue and perhaps, to win brownie points that might fetch some noted awards.

One example is Aakrosh (2010) directed by Priyadarshan where, while dealing with honour killings in a pocket of Uttar Pradesh where the law and the police play havoc instead of implementing order and peace, the caste-schism is also played out between the two investigating officers, namely Pratap Kumar and Sidhhant Chaturvedi who are brought in to investigate the mystery behind three young men who have gone missing. Pratap is a Dalit while Siddhant is from an upper caste and the two often fall out because their perspectives on the oppression are different. The high stakes failed when the film turned out to be a box office disaster.

There are many similar films playing the Dalit card in Bollywood but even if the means are good, the end does not justify the means. In other words, the technical brilliance and artistic excellences are neatly undercut by the pretentious hypocrisy presented in the narrative. Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s Eklavya (2007) is an example in which 800 camels were reportedly used in an action sequence in Eklavya. This spells out the film’s true agenda – glamour and chutzpah. Eklavya presented the radical and “new” Dalit in the shape and form of a bold police officer Pannalal Chauhar who not only asserts his Dalit identity but also bristles against the caste based feudal oppression that still pervades in parts of Rajasthan.

The realistic portrayal

The small-budget films made by relatively young, debutant directors have fared much better in profiling the Dalit identity on celluloid.

Chaitanya Tamhane’s Court (2014) which bagged the Best Film Award at the 62nd National Film Awards last year, it not about the Dalit identity at all. Yet, it subtly pulls us to read into the tragedy of the life of a sewer cleaner who not only has to live within desperate poverty but also has to earn through an occupation – cleaning dirty sewers – that carries a perpetual life risk. He dies while cleaning sewers. They say he was drunk which he is bound to be. Drinking for him is a strategy to keep away from the inhuman dregs his work deals in – human and animal excreta and much more. Others say he did not have the mask a sewer cleaner must mandatorily be given while a third explanation is that he died due to the poisonous gases that had collected inside the sewer. It does not matter which led to his death because his death itself, as much as his life, does not matter.

A still from Masaan (2015). Pic: Shoma Chatterji

Masaan (2015) shifts our vision from the glamorous chutzpah of cities like Bombay, Delhi, Bangalore and Kolkata where most Hindi films are located to a relatively subordinated ‘smaller’ city like Varanasi. The city represents itself through the stories of five characters trapped while trying to discover/rediscover themselves between the ancient that the city represents and the modern the city cannot reject.

The Harishchandra Ghat with its steady flow of dead bodies lit up by the raging flames of the funeral pyres with the doms (chandals) stoking the fires with sticks and beating up the bones and the skulls so that the bodies can burn quickly. One of these chandals is a young and handsome Deepak from a ‘dom’ family who studies civil engineering at night school and helps his father and uncle at the ghat burning dead bodies. He falls in love with a college-going, sprightly, poetry-loving young girl Shaalu Gupta who is from a well-to-family from a higher caste. Does he become a civil engineer and walk away from his family profession. Masaan does not offer easy answers.

The Dalits are not the sole subjects of oppression among the caste-ridden masses of India, never mind that this oppression cuts across the rural and the urban, language, education and social status. The women, who may or may not be Dalit, are equally or perhaps more oppressed and so are the children from the Dalit community.

Torture, and human rights violations committed against certain groups of people have a rather democratic character in our country. All this and much more come across in journalist-turned-director Bikash Mishra’s directorial debut Chauranga (2016) that released across Indian theatres in January this year. The story takes off from a real life tragedy in which a 14-year-old Dalit boy was killed by upper caste men because he had the ‘gumption’ to write a love letter. Chauranga takes this incident as a peg to build up a bigger story placed on a larger canvas of characters located somewhere in Jharkhand.

These are very low-key films that have neither romance nor action nor suspense nor song-and-dance numbers. Everything is real, raw, straightforward and simple. The understated events, characters and their interaction against an authentic backdrop have a lot of potential drama but the directors have refused to dramatize them. No wonder we are mesmerised and fascinated by these honest films. The question is – will these directors continue to make such low-key celluloid statements on significant social issues? One has to wait and watch.

References

Chakravarty, Sumita, S.: National Identity in Indian Popular Cinema – 1947-1987; OUP, Delhi, 1996, p.112.