The Parsis are a community threatened by extinction. As per the 1991 Census of India, the number of Parsis in India has dwindled to 69,601, among whom around 40,000 are in Mumbai alone. The total population of Parsis in India was 140,000 in 1941. Why, then, is the number dwindling so fast?

The answer to this can be traced through the ongoing and unceasing debate between two groups of Parsis – the traditionalists and the liberals. Traditionalists are rigid about not permitting any change, such as marriages between Parsis and non-Parsis which is taboo according to purists. On the other hand, the liberals staunchly believe that such marriages will not only bring about a reversal in the dwindling numbers but will also pave the way for greater mainstreaming of the community.

“If this community dies then a very ancient and precious faith proclaimed by the first Prophet Zarathustra also lies at the risk of slowly fading away. The religion is ancient, yet so modern and has at its core a very simple ethical code that is relevant today,” says Oorvazi Irani who has directed a full-length feature film called The Path of Zarathustra “I wish to draw the attention of the world to this powerful message about my faith,” she adds.

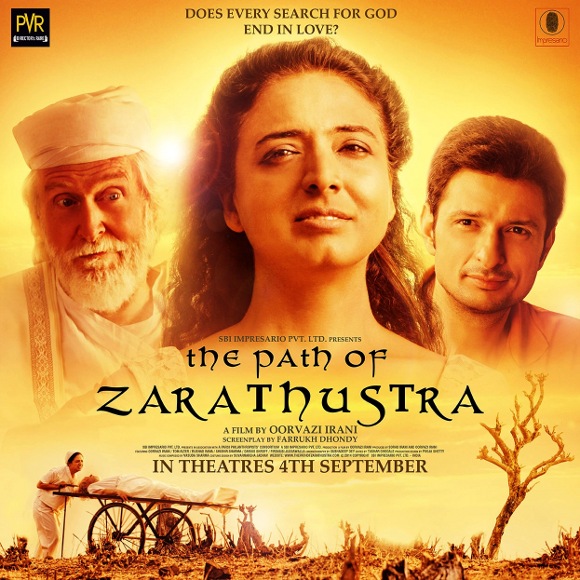

Poster of the feature film The Path of Zarathustra. Pic: Oorvazi Irani

Another point in the larger debate is over surrender of the dead to vultures in the Towers of Silence across the country. While the traditionalists maintain that this practice should be allowed to continue, the liberals are completely against this view. They opine that realities and the climate have changed and the practice of keeping the human corpse as prey for vultures should discontinue.

The vulture population has been declining in India at a rate that ranges between 20 percent and 40 percent every year since 2007. This has resulted in a lean population of vultures, so one dead body takes around six months to disappear after it is placed in the Tower of Silence. Therefore, liberals are convinced that for reasons of hygiene, this practice should be given up completely. As the film shows, the debate goes on without any harmonious solution in sight.

However, The Path of Zarathustra is not just about this debate itself. It also informs people of other faiths such as Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Jews, Buddhists, Jains and others of this relatively less-known dispute. “My main objective in making this film was to bring the Parsi identity and the Zoroastrian faith centre stage for a meaningful dialogue that would dispel many myths that surround our cultural and other practices, and also inform and educate both Parsis and non-Parsis. I am deeply indebted to Farrukh Dhondy, the fearless and respected writer among us who helped me gain the trust of the people involved, including the Parsi Philanthropist’s Consortium which backed this project once they understood what it was all about,” says Irani.

The film opens a bit depressingly with the dying grandfather (played brilliantly by Tom Alter) of Oorvazi (Oorvazi Irani). The dying man hands over to her a manuscript detailing the entire history and myths that surround Zarathustra, the Parsi religion and the origin and migration of the Parsis from Persia to India. He had been writing the manuscript for years and asks her to hold it in her custody till she finds the scholar who is entitled to read it and interpret it.

A shot from the feature film. Pic: Oorvazi Irani

After her grandfather passes away, Oorvazi tugs his body and leaves it covered in the open in the beautiful little town where they lived. She then returns to Mumbai after many years, trying to pick up the threads from where she had left off to take care of her grandfather in his ageing years, carrying the manuscript with her to search for the scholar who is entitled to decipher it.

Irani’s main objective was to make a film on Parsis without repeating the commonly known features of the Parsi faith, the Parsi identity and the Parsi community. The challenge was to situate the film within the contemporary Indian landscape in general and Mumbai in particular “and at the same time, open the dimensions of time and space for a contemplative journey into the past, the present and the future.” Irani names the protagonist after her real name, which might also create confusion in the minds of the audience, especially those who know her quite well.

Though all this sounds very polemic, abstract and spiritual, the film comes across differently, as a visually rich, low-key and poetic journey of a young woman who returns to Mumbai after many years. The focus of this journey is the quest for the scholar who doubles up as Mazdak, a Zoroastrian Priest representing Mazdakism.

Mazdak is a primitive Communist who belonged to Sassanian times. The term “Mazdakism” is derived from Ahura Mazda and poses a challenge to the doctrine or myth of Zurvan (Time). This myth denied supremacy to the creator Ahura Mazda, considered God by people of Zoroastrian faith. The shrewd and diabolic Zurvan in the film is portrayed convincingly by Shishir Sharma. The dual role of Mazdak from ancient times and the intellectual scholar today has been portrayed with great dignity and poise by Darius Shroff.

“My scriptwriter Farrukh Dhondy bridged the gap between the past and the present beautifully with artistic devices to bring out little known historical and heretic characters from the ancient Zoroastrian past. According to Mary Boyce, the heresy was revived in Sassanian times. In the film, the characters appear in modern times symbolising magic realism that the medium of cinema offers,” explains Irani, who found this film to be a great learning experience. Some actors have been used to symbolise both past and present characters because that was the only way today’s Oorvazi, the character in the film, could interact with them.

A shot from the feature film. Pic: Oorvazi Irani

The film is embellished with small sub-plots that shed light on other areas. One is about illegitimate births from the union between a Parsi man and a non-Parsi woman who was later ditched and whose son was left to grope with his true identity for the rest of his life. The character is portrayed by Rushad Rana who plays Percy in the film, adopted by Oorvazi’s (the character) aunt and made to feel one with the family. Percy had proposed marriage to Oorvazi and felt that she had rejected his proposal perhaps because he was illegitimate, though he had been accepted into the Parsi family fold.

This time, however, she has second thoughts and though there is no marriage on the cards, the film closes with the strong suggestion that they will ultimately come together, auguring change that results from the marriage between a true-blooded Parsi woman and a young man who is born out of the union of a Parsi and a non-Parsi.

The film is universal in the larger issues it addresses and yet, is specific in its revelation of the Parsi community and Zoroastrian faith. Irani as director admits that as a practicing Parsi, she is a liberal in every sense.

Oorvazi Irani, director and the lead actor of The Path of Zarathustra . Pic: Oorvazi Irani

“My own sister has married a non-Parsi. I believe that the Parsi faith should not be short-sighted and cling to its superiority complex. I am convinced that one needs to question foundations of beliefs and practices that might have outlived their time in today’s world. We need to look back, discuss and decide which practices to improve upon, which to reinvent and which to let go. To remain true to one’s faith is not to follow and practice rituals that have outlived their meaning and significance. I believe that one must follow what one’s heart holds to be true, without paying undue importance to what is written in some book,” sums up Irani.

The film leaves the viewer with an open conclusion about existing myths and legends, because neither the audience nor Oorvazi the character is informed about what the manuscript actually says. This is rendered superfluous because it is a sacred text.

The Path of Zarathustra is a gentle, slow-paced and subtle film that does not raise its voice to make a point or raise slogans or take sides. Yet, it comes across as a pleasant surprise, belying expectations of it becoming just another film on the community. It allows the viewers to absorb and understand and feel.

Most of the film was shot in and around Mumbai and in authentic Parsi locations with a few scenes on studio-constructed sets. The cottage of the grandfather where the film begins was shot in Vasai near Mumbai at an ashram owned by a Parsi gentleman, who uses it for meditation and study of religious texts. Tom Alter has spoken about how the place inspired him to get into the character and surrender to the role and the moment.

The actors liberally drawn both from the Parsi and non-Parsi communities have aptly taken the film’s message across without melodrama or exaggeration. The music is mood-centric and low-key and the editing is seamless. But what takes one’s breath away is the outstanding cinematography and lighting by Subhadeep Dey which shapes the final film as it comes across on the big screen.

The Path of Zarathustra is an independent film and needs a nurturing hand in the commercial market space. In India, the film was released under the PVR Director’s Rare Initiative, which encourages meaningful cinema, beyond the dictates of commerce alone. Though the film is basically targeted at the Parsi audience that will feel a natural attraction towards it, the director would not like to restrict it to a Parsi audience and encourages non-Parsis to watch it too.

“It would also dispel the myths around the clichéd Parsi persona, presented as a stereotype in every other Hindi film, as one who is eccentric, speaks with a strange and funny accent and is an exaggerated and caricatured version of the real Parsi,” says Irani. She hopes to release the film in the US with the support of the Parsi community and then enlarge the vision by showing it on television, VOD and possibly have a DVD release too.