When asked to choose one book on the environment in India which we - the editors of Biblio - would single out for special mention we unanimously selected Churning the Earth: The Making of Global India (Penguin/Viking, 2012) by Aseem Shrivastava and Ashish Kothari.

Shrivastava is what Ramachandra Guha would call a “freelance academic”, an environmental economist who has taught in the US and Norway and is now writing a two-volume treatise on the environmental ideas of Rabindranath Tagore. Kothari is a founder-member of the NGO Kalpavriksh, which famously doesn’t give its staff any designations. He has also coordinated India’s National Biodiversity Strategy & Action Plan, which relied on a unique participatory approach. He has authored and edited over 30 books and is one of the three sons of the illustrious social scientist Rajni Kothari.

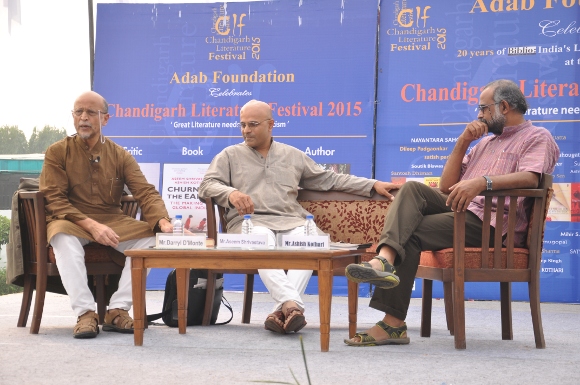

I chaired a discussion between the two at the Chandigarh Literature Festival 2015, and asked whether they had ever imagined that things would turn out as bad for the environment as they now have. Shrivastava agreed that he couldn’t have predicted this, but clarified that it wasn’t because of one party or person but the overall framework, the entire development paradigm was to blame.

Darryl D'Monte (left), Aseem Shrivastava (middle) and Ashish Kothari (right) at the book discussion, Chandigarh Literature Festival 2015. Pic:Adab Foundation

In the book, he said, they traced the trajectory back to Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru who was playing the same game as Narendra Modi now is except that the latter is doing so in double-quick time. The thrust was to ignore the interests of up to three-quarters of the people of India, imagining that what was good for the elite was good for the country.

Kothari addressed his remarks to the large number of school students who religiously attended most of the festival sessions. When he was a student a little older than them in Delhi, he recounted, air pollution was already rearing its ugly head, and they started some activism on that front.

If one looked at Delhi [the world’s worst-polluted city, according to the World Health Organisation] today, students in Chandigarh were lucky because they could escape the pollution onslaught. If they were studying in Delhi, however, at least one in three would suffer from lung diseases by now. So the situation over the last three decades had gotten much worse.

However, the networking that was earlier taking place between NGOs acting on behalf of the adivasi communities and their counterparts in Europe – for example, against the Vedanta company owned by London-based Anil Agarwal, which was stopped in its tracks from mining bauxite in Niyamgiri, Orissa – was now difficult, given the crackdown on Greenpeace and other NGOs.

It wasn’t only the hard-fought green laws which were wrested by people’s struggles that are being threatened but there is also an attack on the freedom of speech and dissent, Kothari observed. As chair of the board of Greenpeace India, the registration of which has been cancelled for very frivolous reasons, he was in the thick of this battle. The actual reason is that Greenpeace is challenging the mode of development which is described in their book. It is not only a challenge to the government but to the cronyism of people who are making enormous profits from this kind of destruction. People who challenge this can’t be tolerated nowadays.

I remarked how the Intelligence Bureau had said that between 2-3 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was being lost due to the activism of groups like Greenpeace. Actually, the facts are quite to the contrary. Even if one takes World Bank figures, it has calculated that the environmental degradation of the country has cost it 5.7 percent of the GDP. Civil society hadn’t woken up to the need to safeguard our environment.

Shrivastava agreed and pointed to the very real reasons why the rich and middle class needed to worry about the poor. In the last 25 years, there had been a precipitous decline in compassion for the poor, which could only be tolerated by a country like the “Untidy State of America”. Even from the long-term interests of the rich, it made cardinal sense to worry about the state of the poor.

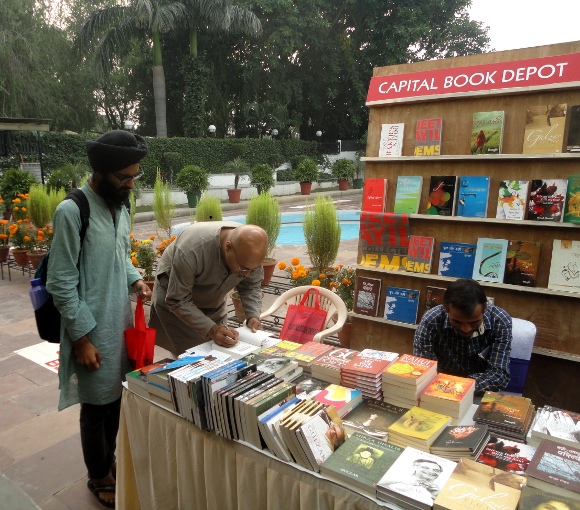

Book signing at the Chandigarh Literature Festival. Pic: Alok Srivastava

If one looked at income and asset inequality in the country, it had been rising dramatically. [In October, it took the prescience of none other than an international bank, Credit Suisse, to point out that the richest 1 per cent of Indians owned 53 percent of the wealth; the share of the top 10 per cent was as much as 76 percent.]

“The poor are pushed to margins of existence where their indifference to nature only grows so that they are going to plunder the last litre of water, the last tree, the last animal in the jungle.” said Shrivastava. The rich, reacting to environmental challenges like air pollution, are going to resort to private “solutions”. In the next five to ten years, people are going to buy oxygen cylinders in Delhi at Rs 700 a cylinder. All of us who buy these cylinders will consider it value-addition and GDP growth. Neither Modi nor Kejriwal has the toolkit to tackle this problem because they are working with the wrong business model.

Kothari mentioned that he was visiting Niyamgiri, the site of the aborted bauxite mine, in Odisha in December. It was a very important struggle because Dongria Kondhs, facing extinction, were raising not just social and economic issues but also spiritual factors: for them, their mountain was also the source of their animist sustenance – something that middle class activists don’t think about. They won that protracted struggle but also because there was a network of support from NGOs in the country connecting with activists in London. The international opponents, memorably, pictured the adivasis as the Na’vi people under siege from rapacious Humans from Earth who want to plunder their natural resources.

The analogy was taken further when British campaigners demonstrated outside a Vedanta annual general meeting in London by masking their faces with aluminium foil. Bauxite is the mineral which is refined to make aluminium, most of the cost of which is the electricity used to process it, the most energy-intensive material in the world. Kothari believed that we needed to introspect on the connection between the Niyamgiri struggle and our own lifestyles, since we all stand to benefit from the exploitation of such natural resources.

Solutions for future

Both speakers were keen to move on to solutions, “hopeful signs” or – as they say in their book: there IS an alternative. How can people resist the forces of liberalization, privatisation and globalisation – or “LPG”? Kothari cited how he was recently in Andhra Pradesh, where he met up with some Dalit women farmers. Vinodamma has been tending her small plot of 3 acres in a dryland area with no irrigation. She grows a variety of as many as 40 crops, many of which he couldn’t even name. There was bagri, millet etc, a virtual forest.

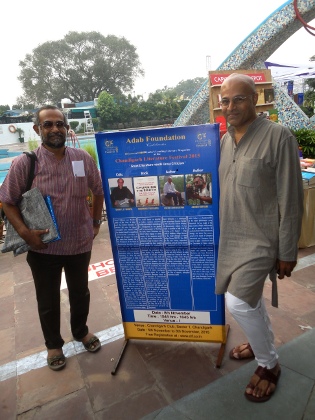

Ashish Kothari (left) and Aseem Shrivastava (right) at the Chandigarh Lit Festival. Pic: Alok Srivastava

This not only met the needs of her entire family but fetched her Rs 2 lakhs a year. She uses no chemicals as pesticides or fertilisers, sows all her own seeds, and her entire investment per year is Rs 18,000. Her own principle is to first feed her entire family and only then look to the market – the opposite of what agricultural economists are advising farmers to do. She is only one of thousands of people who are working with the NGO known as the Deccan Development Society.

A state government institution called Jharcraft in Jharkhand, which has one of India’s largest adivasi populations, promotes traditional handicrafts – metal, bamboo, silk etc -- of up to as many as 400,000 families. They have prospered in just a decade by finding certain jobs in situ. He met a Muslim family whose sons had migrated to a Maruti factory in a nearby town but have returned. Schooling and health are improving.

In Hirve Bazaar, Maharashtra, which has gone beyond Ralegan Siddhi, Anna Hazare’s eco-village, the revival of rural livelihoods and schools through cooperative action has boosted the village economy. People from Mumbai and Pune have actually gone back. Villagers are now asking, in a reversal of the common urban prejudice: how many people can we allow back in?

Similarly the Timbaktu Collective in Andhra has promoted a company of some 2,000 farmers. As a result they are able to brand their produce and sell it on the market; the revenue is distributed equally.

Selco is a social enterprise which has enabled 400,000 poor families in southern India access solar power by promoting social entrepreneurship. These are the hope of the country’s future, not the Reliances, Tatas and so on.

Churning has now gone into four editions and a Hindi version, titled Manthan, is shortly being published. It ought to be made reading for college students throughout the country, at least to get a different perspective of India’s growth. But that’s too much to hope for, given the toxic political environment we live in today.