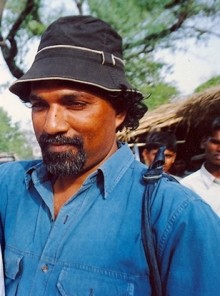

"I met Mahasweta-di by default. Or, should I call it destiny?" asks Joshy Joseph, director of Journeying with Mahasweta Devi, a 51-minute documentary produced by Drik India. Joseph's earlier film, One Day from a Hangman's Life was prevented from screening at Kolkata's Nandan II a few years ago, though it drew large crowds. The film captured a day in the life of Nata Mullick, the hangman who pulled the noose around the neck of rape-and-murder convict Dhananjoy Chatterjee, shortly before he carried out this duty.

When most of Kolkata's intellectuals remained silent, Mahasweta Devi's was the sole dissenting voice. In a letter to DRIK-India, she wrote, "I saw (the film) and was impressed. The treatment is entirely objective. No judgmental attitude towards other questions like whether death by hanging should or shouldn't be there. No moral attitude from the filmmaker. No questions about the morality of a death sentence. It is a bare and savage documentation of a day in a hangman's life. It is just another day. Of course, the hangman is deeply concerned as one Dhananjoy every five years means bread and butter for him, but somewhere he also understands. This film actually points towards the reality, which is today in every viewers' life."

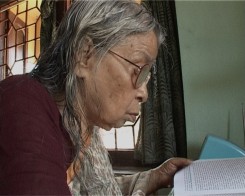

This defense of Joseph's film brought about the first meeting between the director and Mahasweta Devi. Born in 1926 in united Bengal, Mahasweta Devi is one of India's foremost literary personalities. She is a prolific author of short fiction and novels; a deeply politico-social activist who has been working with and for tribals and marginal communities of eastern India for years. Her empirical research into oral history of the cultures and memories of tribal communities is the first of its kind in India. Her powerful, haunting tales of exploitation and struggle are seen as rich sites of feminist discourse by leading scholars. Her innovative use of language has expanded the parameters of Bengali as a language of literary expression, achieved by imbibing and interweaving of tribal dialects into her writing.

Her Verrier Elwin Memorial lecture in Baroda in 1998 led to the setting up of the Denotified Tribes and Communities Right Action Group. The group brings out a bulletin named Budhan. When Budhan Sabar, a member of the Sabar Khedia tribe of Akarbaid in Purulia district West Bengal, was killed by the police on 17 February 1998, Mahasweta Devi, as president of the Paschim Banga Khedia Sabar Kalyan Samity (of which Budhan was also a member) filed a Public Interest Litigation in the Calcutta High Court. The responsible police officers were suspended, a CBI inquiry was initiated, and Budhan's widow was awarded a compensation of Rs.100,000.

Born in 1926, Mahasweta Devi is one of India's foremost literary personalities. She is a prolific author of short fiction and novels; a deeply politico-social activist who has been working with and for tribals and marginal communities of eastern India for years.

Journeying with Mahasweta Devi is not a bio-pic, although Joseph imaginatively weaves in tiny nuggets of this writer-activist-crusader's earlier life through black-and-white pictures picked out of the family album that are turning sepia with time. It offers a picture of this rebellious woman, who at 83, can still belt out her favourite Tagore song spontaneously, or recite Tagore's famous poem Proshno (The Question) ex tempore from beginning to end. The opening frames use a clipping from Ritwik Ghatak's last film Jukti, Tarko O Golpo. It shows three silhouetted, shadowy dancing figures in black against a white background, symbolizing the three elements in human communication â logic, argument and story. Towards the end of the dance, two figures â 'logic' and 'argument' disappear and only 'story' remains.

The film captures Devi in her personal moments, mostly when she is travelling, in a car, inside a railway compartment, talking to the teeming crowds at Nandigram as they rush in to meet her, or at home, talking to the young girl who stands behind her while she combs her hair, and, through large tracts of an interesting question-and-answer session with Dr. Ganesh Devy, who has been working with Mahasweta Devi at the Tejgarh tribal belt in Gujarat for many years. There are no technical gimmicks with editing, sound, music or camera movements.

It is a low-key, understated film where the overpowering presence of the subject in every frame does not add needless glitz and gloss to the film. Nor does Joseph make any reference to her awards and her writing except when she talks about her biography of the Rani of Jhansi or, when she is actually writing at her desk at home.

"I use my cinema as a democratic space where my subject and I are placed on the same platform as equals. Otherwise, it would be difficult for me to make the kind of film I was seeking to make. Mahasweta-di is constantly on the move and that is precisely how I wished to capture her. I am against making a mobile person immobile just for the shooting. I prefer to position myself along and behind the camera instead of inhibiting my subject by bogging her down with my camera. Over two years, we evolved a mutual understanding and she developed respect for me and for my work."

"Journeying with Mahasweta Devi is just a tip of the iceberg of the massive project I have under way. I have recorded her journeys intermittently for the last two years backed by Suvendu Chatterjee of Drik India which has 140 hours of coverage in its archive, basically captured through her journeys. Drik India's team of photographers had been documenting Mahasweta Devi for quite some time. I kept away from the monotonous technique of making my subject sit in front of a camera and keep talking. I wanted to follow her, not direct her. And the Q-and-A session with Dr. Devi came up because he knows her well and could frame questions no one else could," says Joseph.

Joshy Joseph is low-profile, but his portfolio of films is impressive. His films have won four national awards under four different categories on four completely different subjects.

-

Sarang - Symphony in Cacophony won the National Award for the Best Motivational/Promotional Film in 1998. It is an inspiring documentary on a young couple's commitment to revive a valley through organic farming. SARANG - Sustainable Agricultural Research and Natural Guidance - is active in one of Kerala's small villages.

-

In 1999, Sentence of Silence won the National Award for the Best Film on Family Welfare; it is a strong film about the family ethos of the Indian Christian community and the Catholic Church's refusal to permit divorce among them. The film resulted in the enactment of a new statute, the Indian Marriage Act, exclusively applicable to marriages between Christian men and women.

-

After that, Bamboo Blooms won the National Award for Best film on Environmental Issues in 2000. The film is a study on the tribals in the North East and their strong links to bamboo. The flowering of bamboo occurs once in a 40-120-year life span depending on the species. This has a devastating effect on the lives of the local population. The rodent population multiplies uncontrollably (bamboo seeds are presumably aphrodisiacs), devouring crops and leaving the farmers bereft of a livelihood.

-

Wearing the Face won the National Award for the Best Investigative Film in 2001. The film probes the "face" behind the masked faces of Manipuri rickshaw pullers in a humane way. The social fabric, the collective psyche and the economic and political realities of Manipur emerge out as a resultant of this lens-eye witness account of the illegal rickshaw-pullers who keep their faces veiled for fear of being caught.

Joshy Joseph.

Joshy Joseph.

"For me, Journeying is something like the first blower from a pressure-cooker. I have been reading her in print and person for almost two years. The interaction with Dr. Devi was shot in Baroda and brought out such beautiful facts about the struggle between being pulled by all kinds of conflicts and aspiring for a peaceful world that I kept the footage. I could have cut the film to make it either celebratory or extremely critical of the lady. But I didn't do that - I followed her without losing control over my medium, film, and my subject â 'journeying' with Mahasweta Devi and not just Mahasweta Devi per se. This has paved the way for the docu-feature on her that I am now making for Films Division," elaborates Joseph.

Right through the 51-minute film, Mahasweta Devi is her natural self, making her familiar irreverent statements without a by-your-leave. One such is when she says, "I am a rascal and the one who is making this film is also a rascal." How could Joseph manage to bring all this out without his subject becoming conscious of the camera? "It is natural for any human being to become conscious of the camera when the person knows that he or she is being recorded on film. This did not happen here because I moved around her, waiting for her to sit, stand, talk, move, sing, recite, and react for any amount of time without being a nuisance. In course of time, she settled down and became her most candid and natural self," Joseph explains.

The closing frames hark back to the three dancing figures, in a telling comment on the importance of 'story' over 'logic' and all 'arguments.' Journeying with Mahasweta Devi is a film that captures the great poet candidly as she is today, minus the halo of genius and her achievements in the public domain. Unwittingly, it also marks a defining moment in the director's journey as a documentarist. Through the film, we observe a remarkable fact - this strikingly unconventional lady has redefined the word 'celebrity' as we know it and is not even aware of it - and Joseph has done well to capture this in its fullness. For him, meeting Mahasweta Devi was destiny.